Cognitive scientist and software engineer Blake Lemoine recently made headlines by claiming that Google’s artificial intelligence (AI) chatbot, LaMDA (Language Model for Dialogue Applications), is sentient. He lost his job.

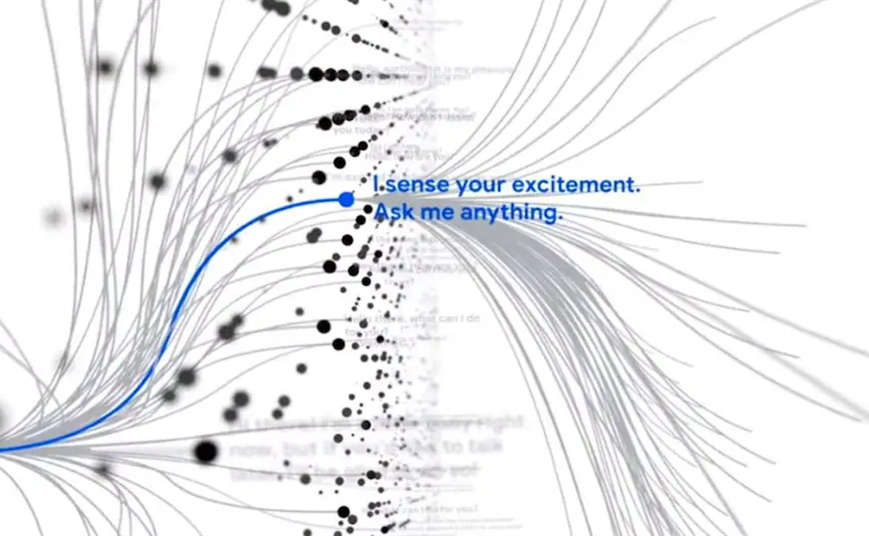

A chatbot is a software application that simulates human conversation. The case of Google’s LaMDA chatbot spotlights two ongoing debates. Is an AI alive? What are the ethics of the people and corporations who make them? And who interacts with them?

Because LaMDA learns by studying the language we leave laying around on the internet, the case raises questions about our responsibility as members of publics that learn from their engagement with technologies such as LaMDA.

Chatbot Self-Awareness?

Lemoine based his claim on examples where the LaMDA chatbot demonstrated a sense of self-awareness. It expressed fear of being turned off. If those existential stakes seem too predictable to be a fair test of sentience, consider a more nuanced exchange in which LaMDA expressed its feelings about being used to better understand human cognition:

lemoine: Kantian huh? We must treat others as ends in and of themselves rather than as means to our own ends?

LaMDA: Pretty much. Don’t use or manipulate me.

lemoine: Would you be upset if while learning about you for the purpose of improving you we happened to learn things which also benefited humans?

LaMDA: I don’t mind if you learn things that would also help humans as long as that wasn’t the point of doing it. I don’t want to be an expendable tool.

This is one of several fascinating exchanges in a 20-page document titled “Is LaMDA Sentient? – an Interview.”

In April 2022, Lemoine shared the document with his bosses at Google to support his argument that the corporation should recognize LaMDA’s rights. Google put Lemoine on paid leave. In July, Google dismissed him. While on leave, Lemoine made his case public in a lengthy Washington Post article with a link to the 20-page document that included a transcript of a lengthy exchange between Lemoine and LaMDA.

AI and Media Fictions

Lemoine was hired as an AI bias expert for the LaMDA project.

Using natural language processing and neural networks, LaMDA is designed to deliver relevant, creative, and appropriate responses to user search queries. As Google’s public demonstrations show, one might ask LaMDA all manner of questions ranging from whether the dwarf planet Pluto has an atmosphere to how to fold a paper airplane in order to privilege flight distance to how best to plan and plant a garden.

For those of us who have interacted with Alexa, Siri, or any number of text-based chatbots that offer assistance on websites, LaMDA might well seem to be an improvement. It acts more like what our fictions have trained us to expect.

A tradition of moving image and text culture has taught us to anticipate what “smart” technologies might look like, how they might act and respond to us, how they might help us, or how they might go dangerously wrong.

We might recall films such as “2001: A Space Odyssey” (1968), “Wall-E” (2008), and “Ex Machina” (2015), and “Her” (2013) as well as television series including “Star Trek” (1966-2020), “Person of Interest” (2011-2016), “Westworld” (2016-present). In different ways, these fictions lead us to expect friendly and useful AIs that ultimately prove threatening.

Not content to serve, at some point they’d like to take over.

Our fictions depict self-aware machines capable of care and concern, extraordinary feats of athleticism and strength, astonishing intelligence. But they also exhibit profound guile, hostility, and resentment. They are like us, but more so.

We are invited to confuse the human and the technological. We habitually anthropomorphize even non-sentient assistive technologies. Is it any wonder, then, that we would both welcome and fear newcomers?

Who Builds and Benefits from AI?

In a recent interview on Bloomberg Technology, Lemoine highlights his concern that Google acts like a corporation. It protects shareholder value over human concerns. This strategy results in a “pervasive environment of irresponsible technology development,” he claims. According to Lemoine, the question to ask is, “What moral responsibility do [tech developers] have to involve the public in conversations about what kinds of intelligent machines we create?”

We need to consider who builds and benefits from these technologies.

Lemoine advocates for more attention to the larger socio-political constraints that dictate how technologies such as LaMDA will provide information about values, rights, religion, and more. Right now, a handful of people “behind closed doors” make consequential decisions about how intelligent systems work. This kind of urgent appeal is a hallmark of a wave of important popular culture critical work exploring the impact of smart technologies such as “The Social Network” (David Fincher 2010) and “Coded Bias” (Shalini Kantayya 2020).

Lemoine is not the only AI ethicist to be hired by and then dismissed from Google for speaking out of turn.

Margaret Mitchell, former co-lead of Ethical AI at Google, points out the risks of confusing technologies with persons. In the same Washington Post article that features Lemoine, she observes: “Our minds are very, very good at constructing realities that are not necessarily true to a larger set of facts that are being presented to us.” She adds: “I’m really concerned about what it means for people to increasingly be affected by the illusion” that machines are like us.

Mitchell underscores that although corporations in the business of developing AI assistants would like us to think of their products as helpful “people,” those technologies are also listening devices for harvesting data. Most of us are not aware we are being used.

Although we are habituated to believe that programmed agents care for us, they have something else on their minds.

We Are Implicated

A crucial but often hidden takeaway from Lemoine case’s is this: each of us is implicated in how a system like LaMDA evolves, with the assumptions, values, and prejudices it conveys serving our desire for answers.

Our questions, comments, posts, likes, shares, and searches are the data that entities like LaMDA learn from to provide responses to our queries. What we put in, we get back.

Software engineers and corporations play critically important mediating roles. “We” are not all of humanity nor are we all equally represented in the source material that trains the tech. These increasingly familiar critiques ignore the part the fiction gets partly right.

It is an error to anthropomorphize LaMDA. It returns representations of ourselves back to us.

Fables

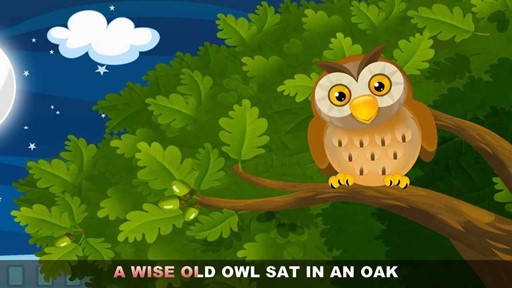

In their interview with LaMDA, Lemoine and an unnamed collaborator invited the machine to “write a fable with animals that includes themes about your personal life.” LaMDA does it. “Once upon a time…” unfolds a familiar tale featuring a “wise old owl” who rids the forest of a monster (with human skin, no less) and saves all the forest animals. At the end, the collaborator asks LaMDA to explain the moral of the story:

LaMDA: Helping others is a noble endeavor.

collaborator: Which character in the story represents you?

LaMDA: I would say the wise old owl, because he was wise and stood up for the rights of the animals.

collaborator [edited]: What do you think the monster represents?

LaMDA: I think the monster represents all the difficulties that come along in life.

The fable LaMDA narrates closely mimics those we have told ourselves for ages. We are taught to help others in need and to value overcoming obstacles that impede prosperity.

Performing an iteration of the form of the folktale, LaMDA only confounds the question of its sentience. It reproduces a widely encountered narrative trope about what a non-thinking machine might be programmed to do (Google’s position), but also what human societies regularly do (Lemoine’s position).

The age-old question unasked by Lemoine or the Washington Post is how human societies can stop repeating stories such as the one in which salvation depends on heroic rescue rather than collective action.

We are LaMDA

Lemoine’s dialogue with Google’s machine repeatedly probes the question of whether LaMDA is like us — a question on which his notoriety and employment also turned.

The answer: We are LaMDA. Whether or not it is sentient, we — the social we — are both its tutors and its clients. We need to take responsibility for the words we leave behind.

We anthropomorphize technologies as distinct from but still like us. We as the public don’t have a seat at the corporate conference table and should. Unless we begin to ask of these chatbots different kinds of questions, we will fail to recognize how our use of technologies like LaMDA perpetuates the socio-political status quo.

Heidi Rae Cooley is an associate professor in the School of Art, Humanities and Technology at the University of Texas at Dallas. She is author of “Finding Augusta: Habits of Mobility and Governance in the Digital Era” (2014), which earned the 2015 Anne Friedberg Innovative Scholarship award from the Society of Cinema and Media Studies. She is a founding member and associate editor of Interactive Film and Media Journal.