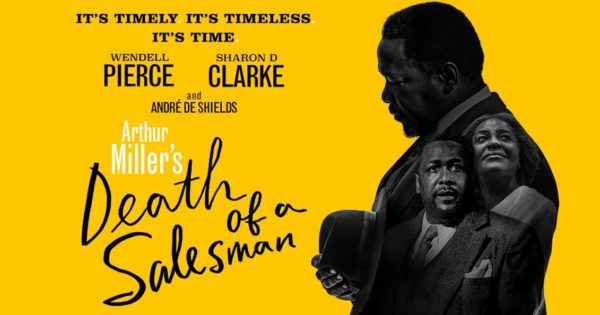

It is clear that the way people react to Arthur Miller’s 1949 play “Death of a Salesman” is as unpredictable as the play itself. Sympathies are pulled in every direction. With the play currently revived for the sixth time on Broadway, let us take a moment to think once more about its troubles and tragic dimensions.

While some see the tragedy of Willy in his refusal to be publicly consigned to failure, others coldly reject him as an adulterous, narcissistic tyrant. They insist that it is Biff who becomes the play’s tragic hero in his recognition of his own mediocrity and inability to stop loving his deeply flawed father. Others turn their attention to poor, cheated-on Linda, darning her pathetically worn stockings and scrabbling away all those years to be left “free and clear” but profoundly and pitifully alone, or Happy, the long-overlooked child who was left to fend for himself and grew up with no moral compass.

Questions abound.

Why isn’t Happy, happy? How far do any members of the Loman family become fully self-aware, including Biff? Why is it so hard to like Willy when they used to weep in the aisles during productions? Should anyone feel sorry for Linda? Was Ben even real?

Having thought long and hard about the play over decades, I have come to a conclusion: the play seems deeply flawed with an array of plot holes, discrepancies, and ambiguous possibilities, yet somehow remains highly successful when produced.

The central problem my students face is their decision that Willy is crazy. This idea precludes them from viewing his decisions as rational and makes it tough to see the play as an authentic tragedy.

I suspect they may simply suffer a failure of imagination regarding what Miller was trying to achieve onstage in a period when only 9% of the nation owned a television and when the majority of Broadway productions were grounded in realism.

What they read as madness was a theatrical technique designed to allow us to share Willy’s internal thoughts. Willy is not insane. He is filled with stress and anxiety that push him to find respite in a rose-colored past that wobbles under his gaze as guilty truths force themselves through.

Some folk dislike Willy’s meanness to Linda and his adultery, refusing to make the empathetic leap necessary to allow such a small man to become a tragic hero. They sympathize with the put-upon wife rather than overlooking this as a cultural expectation that wives in the 1940s did tend to subsume themselves into their husband’s ambitions. They sympathize with Biff as the son who is burdened by paternal expectation and Happy as simply being overlooked. They excuse his caddishness, missing the irony of how they can excuse Happy but not Willy, who is equally overlooked.

Such reactions are too quick.

Linda is no doormat and is exactly where she wants to be, as Miller’s stage direction indicates, “she has developed an iron repression of her exceptions to Willy’s behavior—she more than loves him, she admires him, as though his mercurial temper, his massive dreams and little cruelties, served her only as sharp reminders of the turbulent longings within him, longings which she shares but lacks the temperament to utter and follow to their end.” She may be, as Willy declares, his “foundation” and “support,” but he is her life.

Happy is unhappy because his life has no real aim or stability. Obsessed with sex, he sleeps around, constantly lies to everyone, is dismissive of his family — outright hostile toward Willy — and has no work ambitions other than hope his boss will die and he may get promoted though given his patently lax work ethic, this seems highly unlikely. He behaves like a greedy, self-absorbed child. He admits he is lonely but does not seem capable of settling down. He prefers the thrill of the chase rather than truly discovering, as he asserts he would like a “girl like Mom.” Even he declares that his behavior is “crummy” as he confesses that he hates himself for it!

Meanwhile, Biff is self-sabotaging and another case of arrested development. He is 34 years old, self-admittedly “lost,” and incapable of holding down a job. Does he seriously not realize the effect that his evident failure will have on his doting father? Biff essentially misleads his father, just as Willy is also misled by his brother, Ben, or at least by his memory of him.

Is Ben with his jungle experience and fairy-tale seven sons even real? Linda seems to confirm his presence and success in life, but since much of what we learn about Ben is told through the lens of Willy’s memory, it remains unreliable at best.

Arthur Miller, playwright, “Death of a Salesman”

While Willy had a brother called Ben, the vision we are given, and much of the information we are told, are distortions created by Willy’s need for inspiration and guidance. The underlying callousness of Ben’s depiction should warn us as to how that will turn out.

So, it seems that most problems can be explained away, but perhaps their presence is actually part of the point?

Willy’s life is meant to have holes, which help to emphasize the unreality from which it suffers due to Willy’s inability and downright refusal to face certain truths.

The gaps are important. He has the childish name to better reflect his imaginative capacity and intrinsic self-centeredness. The play’s fragmentation becomes an objective correlative solely for Willy’s state of mind coming apart under the pressures of guilt and disappointment.

“Death of a Salesman” is not a realistic play and was never intended as such. Its plot is full of holes, its characters unpredictable, its truth subjective.

It is a play that can raise more questions than offer answers.

I suspect this might have been fully intentional. Its indeterminants allow for a greater degree of possibility, permitting an audience a variety of paths to a more personalized enlightenment.

Susan C. W. Abbotson is a Professor of English at Rhode Island College. She has published “A Critical Companion to Arthur Miller” (2007), “Student Companion to Arthur Miller” (2000), and numerous articles on Miller, as well as co-authoring “Understanding Death of a Salesman” (1999). She also published “Thematic Guide to Modern Drama” (2003), “Masterpieces of Twentieth Century American Drama” (2005), “Modern American Drama: Playwriting in the 1950s” (2018), and was series editor for twelve Student Editions of Miller’s plays for Methuen Drama (2022). She has also published articles on many other modern and contemporary playwrights in a variety of books and journals.