Julia sat in the basement of the Student Union at the University of Iowa engulfed in a circle of women college students wearing flannel shirts, jeans, and work boots, drinking coffee to power them through a study night at the university library.

It was 1976.

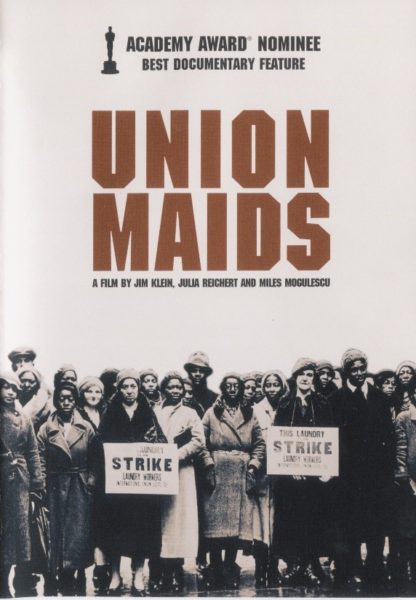

I was a senior in college. I had just watched Julia Reichert and Jim Klein’s “Union Maids” (1976) in the campus theater, The Bijou.

I don’t know who brought her to campus or who introduced her. I don’t remember the discussion. I was just enthralled to meet a woman filmmaker, as the only woman my cinema studies classes ever mentioned was a Nazi (Leni Reifenstahl). I was also excited to see a film about unions, because my grandfather had worked as a labor union activist organizing miners.

I can’t remember if there was a moderated post-screening discussion with the director because, at least for me, something much bigger happened that night, something I had never experienced before: a group of students, some who wanted to be filmmakers, some who were feminist activists, and some who were both, were sitting in a circle with feminist independent filmmaker Julia Reichert. She talked to us as equals, assuming we were all part of the struggle to topple patriarchy, capitalism, and injustice.

No professor or film expert moderated. She did not share the backstory on her filmmaking process or artistic practice. Instead, she talked with us about the politics of mobilizing people to work together.

She rejected the ego posture of a director and instead put our voices first. One of my friends whispered in my ear that Julia (which she insisted we call her) was totally subversive, running the session not as a mentor with acolytes, but as a political organizing meeting.

I was too intimidated to say anything. Political urgency and hope for the future loomed larger than my own words.

Another Version of the Same Story

Decades later, in December 2022, word spread in my feminist media communities about Julia’s death, and different images replaced the one described above, like multiple screens juxtaposed in a museum installation. I wondered how accurate my own memories of Julia in 1976 actually were.

I reconnected with friends from college and graduate school who had their own stories of meaningful, powerful short encounters with her. They worried about how the narrative in Variety and The New York Times describing her as a great American auteur of the working class who won an Academy Award and worked with the Obamas diminished the feminism, political struggle, and a focus on the solidarities of everyday people that were central in her work. And erased her as a feminist committed to community and solidarity.

As my women friends shared fragments of inspiring, deeply grounded interactions with Julia over the decades in quick emails and texts, I started to question some of the details of my own memories of that time at the University of Iowa watching “Union Maids.”

Their emails disordered and disassembled my experiences of her film.

I am certain I saw the film. I am certain I do not know who brought it to campus. I can’t remember who brought me to the theater, but I know I did not go alone and was swept up in a group of about four or five students. We sat in the last row.

In retrospect, I am not certain that Julia the filmmaker was the same Julia in the circle with the students.

One friend said she was not there at all and that it was feminist graduate student activists who shepherded us to the basement and ran the discussion like a consciousness raising group spurred by the film.

Another friend told me that there were many women named Julia there, all talking at once, while many of us bewildered undergrads observed longingly from the back unable to figure out a way to share any ideas at all.

So now, I wonder if, as an insecure 21-year-old unclear about my next path, I imagined that Julia was there because I needed to see a woman making films and fighting power by reclaiming histories of insurgency at a time of transition in my life.

But I also wonder if my memory might have winnowed down a larger collective spirit generated by “Union Maids” into a single film director, my version of what Variety, the New York Times, and Documentary Magazine did?

I have decided that the courageous spirit of those woman union organizers in the film pushed me into that circle and that in the end, it probably matters more that the film engendered this group of politically passionate women than if the real Julia Reichert was actually at the center of it. The memory and impact of this circle of women has stayed with me for decades.

Later, in graduate school at the University of Wisconsin, militant women graduate students older than me heralded “Union Maids” as a landmark feminist film and pushed for it to be on documentary history syllabi along with white male canonical documentary filmmakers such as Robert Flaherty, Joris Ivens, John Grierson, and Robert Drew.

1983

Seven years later, I encountered Julia again at the 1983 Robert Flaherty Film Seminar at Wells College.

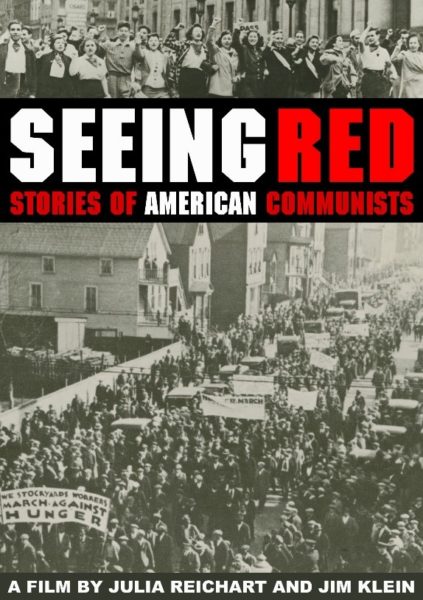

She and Jim Klein screened “Seeing Red; Stories of American Communists” (1983). I was an Assistant Professor teaching film history and theory and arguing for documentary, normally marginalized as a sporadically offered elective, to be included as a required part of our film degree.

It took me a couple of days to jack up my courage to speak with her. I was captivated by her absolute clarity about people and politics, her ability to honor the voices of everyone in the theater or in the groups of people who circled around her constantly. I wanted to be like her: to have clarity and community and people and political struggle.

I drifted accidentally into one of those circles endlessly floating around her when she ended up behind me in the cafeteria as we queued up for greasy bacon and scrambled eggs. I handed her a plate as she held her tray. She asked me my name. I gushed that years ago, I had been on the floor in a circle with her in the basement of the University of Iowa campus union after seeing “Union Maids.”

I don’t remember what we talked about, but I think I squeaked out that “Union Maids” was one of the films that got me thinking about documentary and had inspired me to research documentary theory and history in graduate school.

She was friendly, smiling, asking questions about my life at Ithaca College and in upstate New York as we waited in that line. And then, without any effort, I somehow ended up at a table with a group of other feminists of all ages where we passionately critiqued the sexism of the Flaherty seminar and the male domination of the documentary world.

1993

A decade later, I had edited a special issue of the scholarly journal Wide Angle, and finished a long book project, accomplishments that enabled me to screw up the courage to ask Julia about the formation of New Day Films.

In the mid-1990s, the Flaherty was in trouble with funding challenges, low attendance, and endless controversies that seemed to shred the heart and soul of the entire organization. Ruth Bradley, then the editor of Wide Angle, suggested that Erik Barnouw and I create a quadruple special issue (1996, volume 17, Nos 1-4) to celebrate its survival over 40 years. She began with the name: The Flaherty. Erik Barnouw came up with the subtitle: Four Decades in the Cause of Independent Cinema.

Erik and I invited about twenty scholars and filmmakers, Julia among them, to write essays. She responded immediately, initiated a 90-minute call with me, and wrote a piece whose title summed up how she imagined the world: “Collective.”

In this piece, Julia wrote about the influential filmmakers such as Dusan Makavejev, Emile De Antonio, and Chris Marker that she met at the Flaherty. She describes the lifelong friends she made at the seminar, which she felt was especially important since she made her home in what she called “a remote outpost of the filmmaking world” — Ohio.

She wrote: “The Flaherty gave us: continuity with the past, mentors, and an intelligent ear to our brash pronouncements. It was a civilizing force in the best sense of that word.”

As the tributes to Julia pouring out of the independent and commercial documentary communities note, Julia was perhaps one of the most influential and prolific documentary filmmakers in the United States over a 50-year career.

But auteurist reframing of her narrative as an award-winning director denies those circles and collectives that she mobilized that have sustained not only me, but the entire independent documentary community.

For nearly a decade, Scott MacDonald and I worked on a very long book to chronicle the history of the Flaherty, one of the oldest organizations in the world supporting independent documentary.

Erik Barnouw had always wanted a book or a series of books about the history of the seminar, such an important but unknown part of international film history. After he died in 2001, we finally agreed to his directive and wrote “The Flaherty: Decades in the Cause of Independent Cinema” (2017), the first of our two books on the Flaherty.

New Day Films

As Scott and I figured out timelines, we knew the 1970s were a significant period to analyze in terms of both the histories of the Flaherty and the larger independent film culture. This was a period of intensely charged political filmmaking, film collectives, and the development of new infrastructures of funding, distribution, and exhibition for independent cinema.

And that led me back to Julia, as I had heard many apocryphal stories from Flaherty Seminar elders like Erik Barnouw and Barbara Van Dyke and feminist scholars like Julia Lesage, coeditor of Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Media, about the connection between New Day Films and the seminar.

I reached out to Julia, but she was very busy working on a big film at the time. I told her I just needed a short call to fact check in order to get the story right from the ground up.

She told me that the two of us needed more than a quick fact check; we needed to talk. She wanted to give us both time to unwind into deeper conversation.

So, we had two or three conversations over the course of about two years. I sought out her help to flesh out the vague primary source documents I had discovered and untangle the story.

Julia helped me to see the way in which the emergence of New Day was propelled not by filmmaker narcissism, but by something else much larger and more powerful: debates and struggles to change the entire racist patriarchal system of cinema.

Here is what I learned from her, now chronicled in the first Flaherty book.

In the early 1970s, Willard Van Dyke, then President of the Flaherty Seminar, pulled the seminar’s programming away from Frances Flaherty’s focus on the lyrical and the poetic to a more outward direction. He brought in independent film, animation, experimental, and politically engaged filmmaking from African Americans and women and opened the seminar up to films from the flyover zone between New York and Los Angeles. Feminist filmmaking luminaries such as Abigail Child, Liane Brandon, Joyce Chopra, Amalie R. Rothschild, Holly Fisher, Cinda Firestone, and Barbara Kopple all showed work at the seminar during this period.

At the 1971 Flaherty Film Seminar, women’s anger was mounting over the issue of the Flaherty as a virtually all-male bastion. Julia and other women attendees organized an emergency breakfast meeting with an agenda: a discussion about the importance of women’s issues in documentary.

I want to move away from the auteurism and individuality so pervasive in the contemporary documentary industry, because Julia was so much more than an auteur. I want to honor her commitment to the women’s movement, feminist politics, and the collective by naming the women filmmakers and programmers who attended that meeting: Chloe Aaron, Suzanne Baumann, Kit Clarke, Nadine Covert, Deborah Dickson, Mary Feldbauer Jansen, Tana Hoban, Victoria Hochberg, Jeanne Mulcahy, Kristina Nordstrom, Amalie Rothschild, Janet Sternburg, Miriam Weinstein, and of course, Julia Reichert.

Julia and Jim Klein, her filmmaking partner for over fifteen years, saw a need for the development of a viable infrastructure to support feminist film distribution.

They had begun self-distributing their film “Growing Up Female” (1971), and through that process they were beginning to find a way to distribute to nascent women’s organizations. In 1971, Julia and Jim met Amalie Rothschild at the Flaherty Seminar and New Day Films was formed. The selection committee for the First International Festival of Women’s Films organized by Kristina Nordstrom met in Amalie’s loft in New York City. The women from that Flaherty breakfast comprised almost the entire selection committee.

That fall Julia and Amalie saw “Anything You Want to Be” (1971) submitted by Liane Brandon. This humorous film explores a teenager’s collisions with gender roles. One of the most popular early feminist titles, the film circulated widely among feminist organizations and is important historically. They thought the documentary would be a perfect film for New Day, which from the beginning operated as a collective to connect films to progressive social movements.

In January 1972, Julia, Jim, Amalie, and Liane put together their first mass mailing for the collective’s film brochures under the banner of New Day Films. So 2022 was not only the year that Julia died, but also marks the 50th anniversary of New Day Films.

Beyond the Auteur to the Collective

As I thought about Julia and her large body of work in preparation for writing this piece, I knew I needed to dive beneath the tributes that frame her as an Academy Award-winning director who earned her way to indie documentary industry prestige.

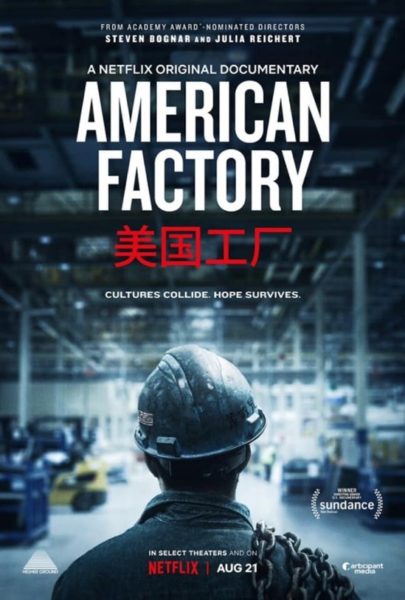

I realized that her films such as “Growing Up Female” (1971), “Union Maids” (1976), “Seeing Red: Stories of American Communists” (1983), “Last Truck: Closing of a GM Plant” (2009), “American Factory” (2019), “9 to 5: Story of a Movement” (2020) represent so much more than the individual vision of a director. They form a circle where everyday people have agency and power because they connect and join forces.

Most of her films were collaborations with Jim Klein and later, Steve Bognar.

Julia’s films reject individualism, narcissism, isolation, and pessimism. They present a deeply feminist vision of America that shows us how hope resides in loyalty to others and to collective action.

They excise antagonists and protagonists and a single hero and instead, show us that the power of the many always wins out over the solitude of one.

Finally, they carry on Julia’s clear, grounded politics: her conviction that struggle, solutions, and solidarities are what matter most.

Patricia R. Zimmermann is the Charles A. Dana Professor of Screen Studies and Director of the Finger Lakes Environmental Film Festival at Ithaca College in Ithaca New York. The author or editor of ten books, her most recent are “Documentary Across Platforms: Reverse Engineering Media, Place, and Politics” (Indiana 2019) and “Flash Flaherty: Tales from a Film Seminar” (Indiana, 2021). She is Editor-at-Large of The Edge.

Header photo by Yannis Pal under Wikimedia Commons.