Of course it is a joy that Chantal Akerman’s “Jeanne Dielman 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles” (1975) has been chosen as the best film ever by the 1,639 critics, programmers, archivists, and academics who answered this year’s survey. The British magazine Sight and Sound has conducted this survey once a decade since 1952.

It is exciting not only because it is a film directed by a woman on a list historically dominated by men but because of the vehement and radical way in which Akerman’s film breaks all expectations of classical storytelling and institutional modes of narrative.

Other films on the 2022 list are surprising for similar reasons. Names like those of Claire Denis, Barbara Loden, Maya Deren, and Agnès Varda have become more highly esteemed by voters, opening a paradoxical space for the most daring and experimental cinema to enter the canon.

What is quite surprising in the list of 100 films is that there are no Latin American films, only one in Spanish (“The Spirit of the Beehive,” Víctor Erice, 1973) and none in Portuguese.

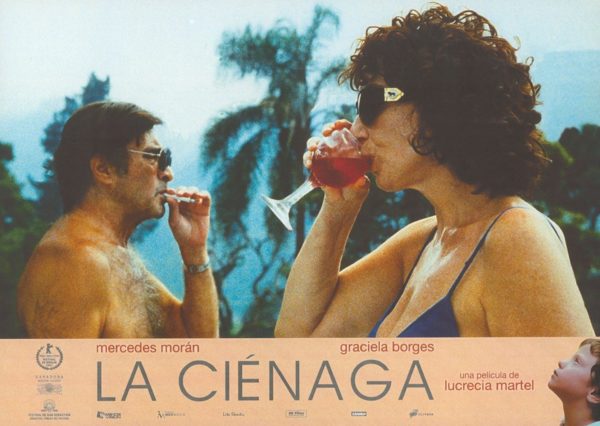

“La Ciénaga” (Lucrecia Martel, Argentina, 2001)

Did the magazine’s attempt to broaden its voter base and be more inclusive in terms of geographical origin fail?

The truth is that this does not seem to be the reason, as there was an important number of Latin American voters or those with a clear relationship with Ibero-American and Caribbean cinema. The result can be interpreted as a warning sign not only for the cinema of the region but for the critics, the festivals, and the academy of the geographical, linguistic, and cultural areas in which we work.

What relationship do we have with our own cinematographic traditions?

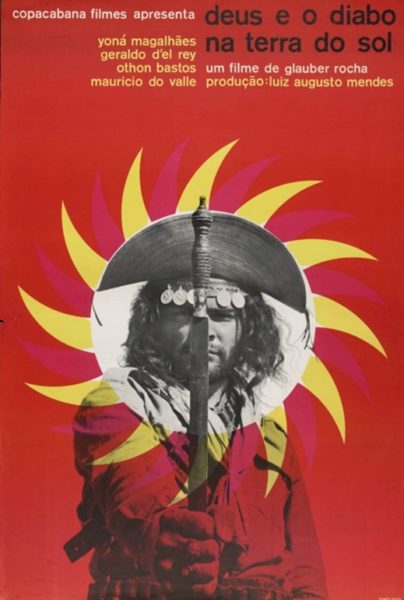

“Deus e o Diabo na Terra do Sol” (Glauber Rocha, Brazil, 1964)

The almost total erasure of Spanish- and Portuguese-language films may also be a sign that Ibero-America and the Caribbean no longer count in the inclusion policies decided by the Anglo-European centers or that they no longer matter in the way they did in previous decades. In addition to the increase in the presence of women directors, the Sight and Sound list also includes African and Asian cinemas — although not in the proportion one would expect. Nonetheless, there is some “news” of their existence.

This warning signal contains a challenge and issues demands to those of us who work with cinema from these regions.

Some very urgent work is in order to resist this erasure of all cinema and of its languages in a region.

We need to create our own histories of cinema beyond the usual national histories.

We need to write more books about our own film history as well as other film histories.

We must curate works from where we are and on our own terms that can travel and be used as a reference by the hegemonic centers.

We must establish more South-South dialogues without giving up the South-North dialogues. We must put pressure on the North.

We must restore more films.

We must reread the past and bring it to the present with renewed critical energy.

In short, we must use all possible forms of intervention into the processes and institutions of circulation of Latin American and Caribbean cinema.

Once and for all, perhaps these actions will begin to change the loathsome idea that Europe and North America invents cinematographic forms and languages that the rest of the world only tries to imitate.

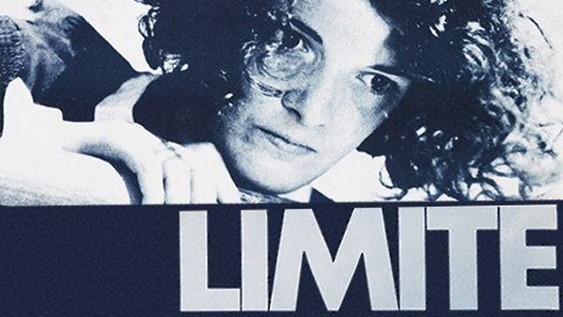

“Limite” (Mário Peixoto, Brazil, 1931)

Assumptions based on this notion abound:

That we only make cinema of urgency and survival to translate our plunder to the plunderers.

That our cinemas are informative, transactional, and only interesting as national or territorial allegories that verify what is already known.

This is only a hypothesis: Latin America and the Caribbean may have ceased to be interesting for those external gazes. Yet those of us who live here know that no foreign gaze can fully define us.

This world of ours is also a laboratory of the imagination, a space to work, something under construction and therefore open, porous, vital.

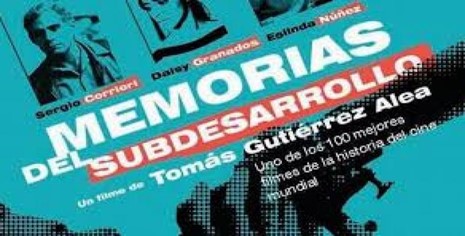

“Memorias del subdesarrollo” ( Tomás Gutiérrez Alea, Cuba, 1968)

We are not going to solve European and North American myopia.

An asymmetrical relationship has marked our contact with that imperial imagination. If we have to assume the task of freeing them from that myopia, we will again be trapped in the anxious cycle of living for someone else.

If Europe and North America declare the end of cinema, the end of history or closed and hermetic forms of cinema and history, or the history of cinema, here in Latin America and the Caribbean we continue to live and make history with fierce creative joy unencumbered from those so-called closures!

To read this article in Spanish, view it on Cinema Tropical’s website.

Pedro Adrián Zuluaga is a journalist and film critic. He was Program Manager at the Festival Internacional de Cine de Cartagena de Indias-FICCI from 2014-2018 and editor of the film magazine Kinetoscopio. He is the author of the books “¡Acción. Cine en Colombia!” (2007); “Literatura, enfermedad y poder en Colombia: 1896-1935” (2012); and “Cine colombiano: cánones y discursos dominantes” (2013) and of numerous essays and articles for Colombian and international press publications. In 2018 he won the Simón Bolívar National Journalism Prize (Colombia) in the category of Print Criticism.

This essay is translated from Spanish by Samuel Didonato. Deep thanks and gratitude to Carlos A. Gutiérrez and Cinema Tropical for their support of The Edge.