This is a meditation. It has been unevenly in process for most of my life. I cannot remember a time that I was not working at becoming an anti-racist feminist. It is a long process with no clear trajectory, much like the political and historical story of this nation establishing and sometimes reforming its racist misogynist structures. But this moment feels different to me.

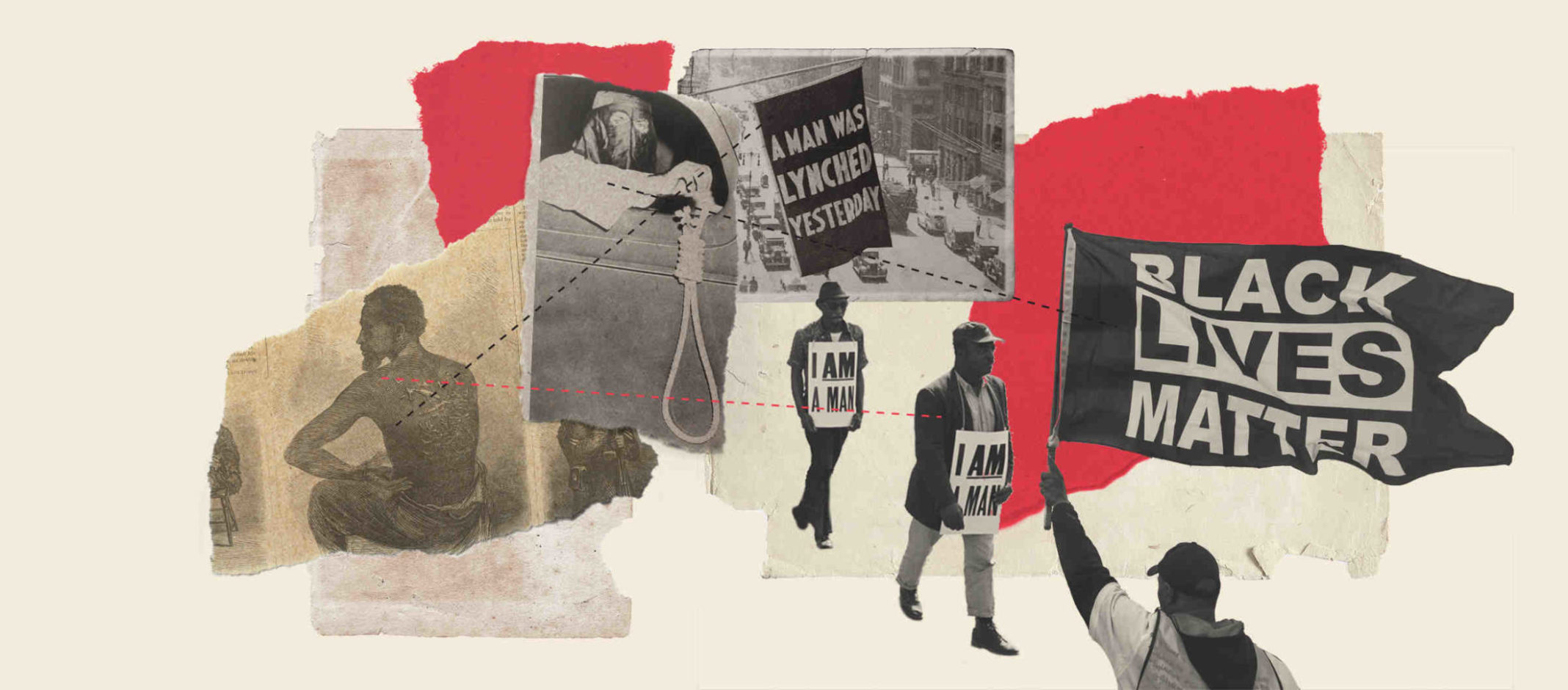

This work has been a conversation with the Black women in my life through our friendships and/or their writings: Angela Davis, Beverly Guy Sheftall, Barbara Smith, bell hooks, Mariame Kaba, Kim Crenshaw, and more recently Tamura Lomax, Tera Hunter, Brittney Cooper, Imani Perry and Saidiya Hartman. But now my newest thinking about how trauma and grief connect with the lives of incarcerated people and the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor and the Black Lives Matter movement, along with the Covid pandemic, further exposes the cruelty of U.S. racism in a new fashion, even though it is not new. And the offerings on so many streaming platforms that reveal the rich Black intellectual life that we can all thrive with—Exterminate the Brutes, The Underground Railroad, High on the Hog—have further exposed the barbarity. So, I think our culture is maybe almost at the end of the something; and also, almost at the start of something really new.

It feels like this deep upheaval is so palpable that it will really matter this time. That this time it is cracking the foundations and that the structural apparatus of racism is faltering by a million little cuts/stabs. How to coalesce all this is the challenge. And, maybe this framing will help us think more deeply about reparations and what it might do and cannot do.

How can white people think of really uprooting the misogynist racism that poisons human life? How can we repair life with and for black and brown and yellow and all poor people? And the remaking must be deep and thick.

Maybe, finally, enough white people are willing to look and really see the violation/s and barbarity of the foundational base of chattel slavery and the dispossession of Native land and its people. And enough does not need to be most of us; however, many will have to do. The deep look requires a fearlessness to find and feel sadness and pain and grief. W.E.B. Dubois and James Baldwin always dared us to look and see.

I am sure that the hundreds of thousands of Covid deaths in the U.S. are a part of this new reckoning. That the trauma of death and dying and the racial unfairness of how we die have pushed us to a new honesty and fearlessness about the urgency of now. That the crushing burdens of the pandemic, especially on women of all colors and then more devastatingly yet again on BIPOC, rev up the yearning for something that can be liberatory.

Why does this moment feel different to me? There have been promises to improve before through civil rights law. There have been attempts to create equity. Why does it maybe feel like fundamental change is going to happen this time? Because the changes in consciousness appear to be big and broad. The commitments to another world seem deep. But what might the step/s be to make sure this is not just another moment to avoid a fundamental restructuring of racist misogyny?

Maybe consciousness is part of the structural change that so many of us are demanding. Maybe many changed views begin to disable the systems in play. Maybe the clear divide between thinking and doing; between individual selves and the apparatus they inhabit is not a clear divide.

If white people open ourselves to the wounds, to the hurt, to the trauma of Black life and try and really absorb it we extend ourselves to others who live the hurt. We become closer to them. There is no simple dividing line. Humanity gets bigger. This is the politics of white grief—that we do not fear it but rather find it, look deep at it, and use it to overturn history.

As such grief and life, itself, are embedded with each other and recognized. Instead of fearing death and its truths we reckon with it. When we find a balance and connected relationship between grieving the traumas that whiteness creates then it is possible to see and remember and not forget the trauma.

After watching “The Underground Railroad” by Barry Jenkins (on Hulu) I wondered about each enslaved person:

How did you first know you were enslaved?

What did you think the sounds the white men were making were? Did you know they were speaking another language?

When did you know you needed to learn their language?

How did you start to learn it?

When did you think it was forever?

When was the first time you wanted to kill your master/mistress?

Did you hate them all the time? Every minute?

Did you think you would survive?

When did you stop caring if you did?

Did you want to strike back each time you were abused?

Did you cry yourself to sleep at night? Every night?

Did you fear rape each day, every minute? Were you angry all the time?

Did you think about escaping every minute?

Slavery—this abusive pile of everything vile—was foundational and it was also an abomination. It was not simply a contradiction to our founding ideals. White people must really recognize white privilege as the unfathomable cruelty it is so that reparations are fully radical and not simply an attempt to patch together a foundational racist system that cannot be fixed.

To silence or avoid what my white privilege has felt like to someone/anyone else distorts whatever I might think I am seeing. An absence is not neutral, it distorts whatever is visible. And, then we don’t know what we don’t know and what we know—what is put forward, is not a truth. It is white ignorance. “Whitewash” is truly a white washing of knowledge, knowing, feeling, wondering. I thought this as I watched the Netflix series “High On the Hog,” about how African American cooking is foundational to American cooking—from the foods themselves, to the chefs, to the slave routes that brought these foods here; or the Black cowboys (boy—as in slave) who brought five million cattle to Texas.

For reparations to go deep enough I need knowledge of the depth of the harm. Racism is a wound that has a history—when you suffer hatred or discrimination you do so with its historical force if you are BIPOC. It is not just individual, but it is structural and historical. It is why Critical Race Theory (CRT) is so essential to this project of finding racialized/racist history. CRT is, as a method of study and discovery, crucial, especially for white people.

So, CRT is a needed remedy. It is looking to see and know more about the architectural base of racism. And this discovery route is different for white people and people of other colors. White people must find and see themselves in this exposure. As white people we need CRT more than anyone and it is exactly white people who are wanting to shut it down. There must be some truth here to reveal.

Knowledge is both individual and structural. So, as we individually expand our minds and hearts, the structures we are embedded in need shifting. Changing consciousness and knowledge is a precursor to reparations. It is not structural in and of itself but begins the connection between individuals and the institutions and governments they are implicated in.

Massive shifts of knowledge and knowing are a first step towards accountability. As more countries reveal their role and complicity in white supremacist practices/brutality like Germany apologizing for its genocide in Namibia with the erasure and bludgeoning of Herero and Nama communities, we move to the next query: what really would allow for repair?

For the Dutch to see and acknowledge their role in the slave trade is a step towards recognition and responsibility to upend the connection. This uncomfortable knowledge requires a restructuring of what remains. The remnants of slavery which continue must be expunged. As such, reparations are a first step toward racial justice.

So, what might reparations mean? Reparations are not a sufficient apology. They are not an act for forgiveness. They are not a remedy. They are a step towards accountability and movement forward towards racial democracy. They mean white people take responsibility for what has been done in their name and for their brutality. It is a step towards finding and building a shared and radical humanity.

To repair is to reimagine human connections and possibility. To be able to know and grieve the wrongs done is one of our most genuinely human potential qualities—it allows us to feel and see and know and imagine a more complete humanity. So as a white person I stretch to know more of the wounding white supremacy has caused my brown and black comrades.

I want to radicalize grief and then this is not guilt, which is a dead ended feeling. Guilt suffocates and divides. Whereas grieving allows us to see one another’s humanity—it becomes an interracial camaraderie.

As a white woman, the more I feel and understand the wound and my complicity, the more I keep pushing out and through new understandings. The racist violations span through prisons, voting access, schools, housing, all of it.

As Cori Bush demands, making Juneteenth a national holiday is not enough. It must be Juneteenth AND reparations; Juneteenth AND end police violence + the War on Drugs; Juneteenth AND end housing + education apartheid. It’s Juneteenth AND teach the truth about white supremacy in our country. Black liberation in its totality must be prioritized and acted upon.

The limits, the contradictions, the lies of liberal and neo-liberal democracy are more exposed than maybe ever. Liberal democracy cannot be fixed. This exposure erodes once important defenses of freedoms over equality. Now equality of class and race and genders must be addressed.

Reparations are not to uphold the old system; to rig it up to withstand the assault; to mediate. Reparations must be understood to undermine the old system of white supremacy—its knowledge systems, its cultural appropriations, its plunder, its erasure. The commitment must be to abolish the excesses of misuse and abuse and to find new ways of relating to humans and organizing life processes.

So besides opening our hearts and imaginations to know that repair is a long slow slog we must think about starting with a redistribution of the goods and benefits. Stacie Marshall—a young white woman who inherited a 300-acre Georgia farm located on stolen Native land and at one time worked by enslaved people—wonders how to make good on this despicable history. Does she redistribute land and/or monies to try and redirect the harm? And how does she trace the families of the people harmed?

We need a national commitment to recreate the possibilities and opportunities. Let us start with eliminating educational, medical, and housing debt. Debt abolition can be the start for reparations. As such debt abolition will begin the repair needed to build a new radical democracy. As such, abolition creates a forgiveness that creates possibilities out of accountability rather than punishment. Don’t respond by saying this is impossible. Our political imaginations must find a way to make the impossible, possible.

Steven Bradford, California state senator, says in defense of reparations: “We have lost more than we have ever taken from this country. We have given more than has ever been given to us.” Now, it is white people’s turn to really give back what should not have been ours in the first place.

Zillah Eisenstein is a noted feminist writer and has been Professor of Politics at Ithaca College. She is the author of numerous books, including “The Female Body and the Law” (UC Press, 1988), which won the Victoria Schuck Book Prize for the best book on women and politics; “Global Obscenities” (NYU Press, 1998) and, most recently, “Abolitionist Socialist Feminism” (Monthly Review Press, 2019).