As I walked through an academic building on the Ithaca College campus a few weeks ago, I peeked into a class and saw something that surprised me. This image is now so pervasive, I should not have been at all surprised.

The professor stood at the head of the room facilitating a discussion. In the second to last row, a student watched a World Cup match. I couldn’t get close enough to see the score.

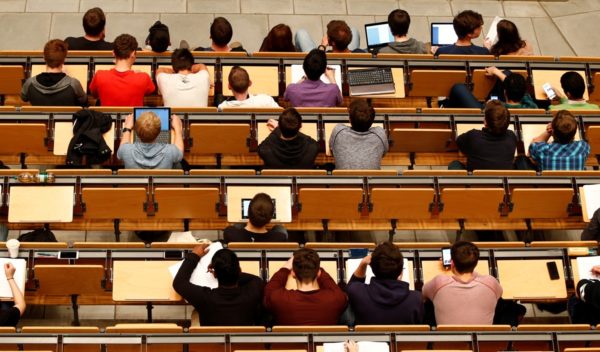

That same week, I sat about halfway up the auditorium in a class I co-teach. My colleague delivered the day’s lesson. A student’s laptop activity distracted me.

The student moved from website to website with astonishing speed. NYT crossword, Wikipedia, the news (but no World Cup stories), email, Instagram, Twitter, and back again. The student rarely stayed on the same page for more than a minute.

Even though I couldn’t discern any details, I found it impossible to not watch the student’s screen. I lost track of my colleague’s lecture.

These two examples are not aberrations. They illuminate the new normal.

It is pointless to speculate if this screen obsession is a byproduct of COVID which forced young people to do everything on screen.

This fall semester, I realized that my competition with the French national team, Randy Rainbow, or the new baby elephants at the Syracuse Zoo zapped enjoyment out of my teaching.

Humor helps. I don’t mind being a bit of an entertainer in the classroom.

Sometimes I stop mid-sentence. I ask a student buried in their laptop to tell me what I just said.

I joke about kitten videos just to jolt them off their screens. I remind them that the most important person in the room is me — and that they should pay attention.

When I speak with students about electronics in class, they generally arrive at similar conclusions. They have misused their laptops in class. They have been distracted by others on iPads, iPhone, laptops. They would be more than happy to learn in an electronics-free space.

Their attitudes align with a national trend. Often led by young people, Luddite clubs are popping up around the country,

No students have ever reported seeing inappropriate content to me. But it would not surprise me if this material trickled across these screens. For full disclosure, a few weeks ago I recently attended a meeting on Zoom where I also simultaneously watched a World Cup match. We are all multitasking.

By the end of the Fall, I had run out of both jokes and patience.

Whoever thought laptops constituted a universally good idea in classrooms was either on the take from the high-tech industries or had never been web surfing on their computer during a meeting.

The 2017 study “Logged in and Zoned Out” in Psychological Science showed that non-academic internet use was common among students who brought laptops to class. It was inversely related to class performance. After accounting for motivation, interest, and intelligence, this relationship was upheld. Class-related internet use was not associated with any benefit to classroom performance. I could cite studies left and right.

My very unscientific study of the matter has brought me to the following action plan.

In my spring semester classes, I will ban all electronic devices.

I will print readers. I will provide VoiceThreads for any of my PowerPoint-based lectures. I will provide discussion notes to any student who requires them. It helps that my classes are all discussion based.

Canvas, that latest technological miracle that promised to transform teaching and learning, will store films, grades, and the syllabus. That’s it. Writing assignments will be submitted on paper. When we need to conduct library research or other very specific projects, I will allow the dreaded machines to make an appearance. I will also make a point to limit my own use of PowerPoint.

Most importantly, I realized that like any difficult task that brings rewards, students will thank me for making them live electronics-free for a few hours every week.

Jonathan Ablard is a professor of History at Ithaca College, Ithaca, New York. He is the author of “Madness in Buenos Aires: Patients, Psychiatrists, and the Argentine State, 1880-1983” (Ohio University Press and University of Calgary Press, 2008). He has published numerous articles on the Argentine military, Argentine conspiracy theories, and Latin American nutrition.