I was punched in the gut. It hurt.

I thought this would be the seminar session to bring all the theories and histories of documentary across analog and digital together with a big political and epistemological impact.

But I should have summoned my semiotic training to read the signs better.

Honesty

Throughout the semester, a few students did the unthinkable in these post-pandemic times and came to my office hours.

One wanted me to know he put all his energies and time into production classes and working on other students film shoots because he hated to read. One told me that theoretical courses were simply not her priority. She preferred her extracurricular production work, clubs, and peer mentoring. Abstract thinking seemed worthless.

Another told me that he did not like watching anything that was more than three minutes long. He only watched media on his phone. He wondered why a screen studies class even required books, screenings of film and new media, and writing papers, since none of that “mattered.”

More than one insisted that any course that did not lead directly into a hands-on production job right after graduation was a waste of time and money.

Abounaddara Collective site

A student who did show up for class spent every class texting on his phone. When I confronted him and told him it felt disrespectful to our collective work in the course, he replied that he had more “important things to do than participate.”

They all framed their views as “honesty” so that I would know “where they were coming from.” I just listened. I asked questions. A handful dropped by to discuss ideas about documentary and new media forms, which I savored for its rarity.

Who can argue with this kind of ideological opposition to anything intellectual? Hours of these conversations beat me down, hearing from student after student that my course, my labor on their behalf, and even my credentials as a documentary studies scholar did not matter because none of it led to their future fantasy job as a gaffer or camera assistant or screenwriter.

A small handful popped in to complain about the sexism and racism of our program. I asked if they were organizing into groups to analyze and take some action. They said no. It was just how they felt.

The session I was excited for was a class focused on the emergence of radical independent documentary filmmaking during the Vietnam/American War, paired with community-based film and social media from the civil war in Syria. It was mid-April. Blue crocuses and yellow daffodils popped up all over campus in a quilt of bright colors and hope.

The film and new media I showed in class depicted people taking action together, in 1972 Vietnam or in 2022 Syria, to analyze, to confront, to fight those in power, to say no, to survive.

Skipping the American War in Vietnam

I spent about six hours prior to the class reworking my PowerPoint outlining the histories of the American War in Vietnam, the context of mainstream media coverage that hid the realities of war and our involvement in it, and the radical interventionist independent documentary that exposed it. Given the war in Ukraine and the political polarizations here in the U.S., this work felt urgent.

I threaded in all manner of interactions to keep the students engaged, from applying theories, making comparisons, doing close textual analysis, working in small groups, connecting with other historical movements of documentary.

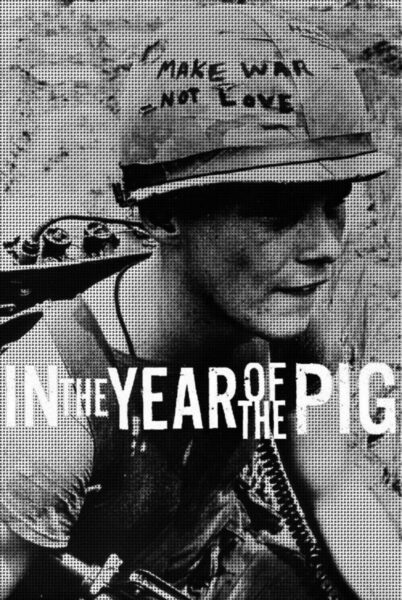

Poster for “In the Year of the Pig” (1968)

I even researched the histories of how some of these works had been shown underground on the Ithaca College campus during the anti-war period of the late 1960s and early 1970s with projectors “borrowed” from the film department for nighttime screenings. They were not screened in any class but as part of political movements to end the war and galvanize students to protest.

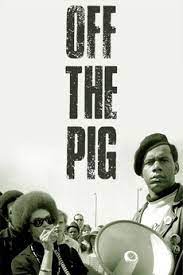

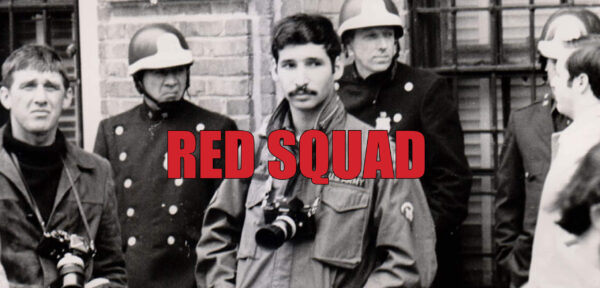

I was excited to discuss “In the Year of the Pig” (Emile De Antonio, 1968), “Red Squad” (Pacific Street Film Collective, 1972) and “Off the Pigs” (Newsreel, 1967), paired with the Syrian anonymous collective posting online shorts about the war on the Abounaddara site.

Poster for “Off the Pig” (1968)

I walked into the seminar room on the third floor of the Roy H. Park School of Communications at 4 p.m. that Monday. Only seven students of the 14 enrolled were there. This was a small class, the kind that pundits pronounce are more attractive to students than the large lectures I typically teach with nearly 200.

In other words, 50% of my students did not come at all and ghosted me when I sent repeated emails concerned about their absences. This was an upper-level class, required for their majors, and taught in an interactive seminar style. Throughout the term, about 25-35% of students were absent on any given day.

Photo by Ponderosapine210 on Wikimedia Commons.

But this evening was extreme. The seminar room was emptied of students. The situation unnerved me and disrupted my psychic equilibrium with a brew of anger and despair.

Absenteeism and Hallucinations

The next morning, my anger had not subsided. It had intensified.

I felt nervous discussing this massive rate of college student absenteeism in public, even though I am not someone who believes in silencing problems. But I could not believe I am the only professor in central New York with high levels of absenteeism.

In my large lecture, 200-person introductory film studies class in Fall 2022, fewer than 40% of the students watched the films on Kaltura, the program that facilitates access to films on Canvas, our learning management system. Students watch on their own, deciding on their own viewing strategies of doing it all at once or in smaller chunks. And faculty can track if they watched the entire film (most only watch 10 minutes) or if they watched at all.

Depending on the day and topic, about 30-50% of the students skipped lecture and discussion. And my bet is that you can easily guess the percentage of A and B marks mirrors the number of students who watched all the assigned films to the end and doggedly attended class and took notes: 35%.

Institutions of higher education around the country and maybe even around the world seem to be dedicated to producing a mass hallucination that everything is back to some new version of normal if only faculty would understand how to adapt teaching styles to this post-pandemic, social media-doused generation.

In a way, who can blame them for this fantasy as enrollments drop, popular culture denigrates higher education, and students disengage from intellectual life in unprecedented numbers?

At the end of year, some faculty flood social media, boasting of fantastic student papers and films. They display group pictures of their happy, smiling class.

This public display of student success eerily reminds me of pictures from the 1920s of white hunters posing with elephants and lions they shot on safari. It, too, feels like a bit of a hallucination of academic success and celebration amidst the despair of the moment. Perhaps this visual evidence functions as a new kind of loyalty oath. Who knows.

Full disclosure: I have never posted in public about any student work nor posted group shots with my students. I am not sure why. It makes me uncomfortable.

The Great Disengagement

Since early 2022, a plethora of articles have appeared discussing “The Great Disengagement,” the phenomenon describing college students who do not attend classes, fail to turn in their work, and refuse to participate in class discussions. It’s the college-level version of “The Great Resignation,” where people decided to quit their jobs as a result of the pandemic and other stressors.

In “Student Disengagement Has Soared Since the Pandemic” on EdSurge, the author undertakes a participant observation at a Texas public university. Most of the students in the class were on their electronic devices and not taking notes. Out of 220 students enrolled, only 60 showed up.

Photo by Alan Levine on Flickr.

Many articles push a neoliberal corporate line of reasoning. They note high levels of depression, exhaustion, pessimism, cognitive overload. The solution: sell your class, build personal relationships with students, jettison lectures, design sessions so that the students run the class.

Other articles adopt an even blunter analysis evidencing just how deep the neoliberal corporate invasion goes: the only purpose of higher education is to prepare you for a job and to help you brand yourself.

The “real world” — whatever that imaginary place conjured up by students and bought into by institutions might be — is all that matters. An ethos that elevates transactional engagement pervades, barely critiqued or deconstructed. Students are robbed of the only four years of higher education they are allotted to stretch, explore, live in ideas, change, and experience the growth that comes from intellectual turbulence.

Writing in The New Republic in February 2023, Colby College professor Aaron R. Hanlon contends that none of this training addresses what is vital about the college experience.

He identifies the double curriculum many colleges and universities have instituted. One is about classes, the other about all manner of employee obedience training about wellness, career counseling, resiliency, sensitivity, refining one’s LinkedIn site, and building a resume. He argues that “College is the last opportunity for students to learn how to think and be in the world with a partial buffer from work place demands.”

A Very Unscientific Study

I am neither a scientist nor a social scientist. Both categories of faculty would likely critique my intuitive, unsystematic methods for using a Facebook post about how 50% of my students did not show up so that I could open up discussion with colleagues in screen studies about The Great Disengagement in higher education.

Forgive me, colleagues, for my humanities-inflected ways. I’ll leave it to scientists, social scientists, education specialists, and college administrators who can mount massive surveys of student attitudes to correct my inaccuracies. I will stick to textual analysis.

I worried about disclosing this 50% absentee rate in my screen studies class.

I know some faculty at many institutions sense that administrators are lurking everywhere ready to send professors private emails to scold for postings that are the least bit negative. I know some faculty feel you should only discuss positive things about teaching to avoid being perceived as hostile to students. Some argue that promoting a zealous optimism can create a bulwark against right wing anti-intellectualism.

My own tactic was simple. I shared my story to break the silence about what is happening and see what others thought.

I never expected the response I received.

161 people liked my post about absenteeism and disengagement in screen studies classes. 205 comments ensued, from faculty in Argentina, Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Italy, Nigeria, Singapore, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom, United States, and more. They taught at expensive small private colleges, large Research 1 public universities, elite highly competitive schools, second-tier public universities, community colleges, and art schools.

I heard from senior faculty from my own institution and from around the globe via PM, email, and text who did not feel comfortable going public about the massive absenteeism and disengagement in their courses.

They seemed to feel that the only way to be in public was to display fervent pedagogical dedication, bragging about great students and life-transforming classes. Some had endured angry and sometimes frightening outbursts in class and hostile student evaluations. Some had encountered subtle critiques of their teaching methods from students to administrators. Some felt that the possibility to push students intellectually died five to eight years ago.

I heard from alumni, many now paying for expensive private colleges for their own children, who were completely gobsmacked that students do not attend class.

Cinematographers, editors, producers, writers, and advertising executives were flabbergasted that any student who wanted to work in the film and media industries would not even bother to watch assigned work. They wondered how absentee students who did not watch films could work in these highly competitive industries overflowing with brilliant minds they so desired and fantasized about.

They shared that the classes they remembered from college were their critical studies courses because they transcended technological change, unlike the practical skills they learned in production courses two decades ago that are now out of date. Note: I am reporting here, not bragging.

The Problem

Those 205 comments revealed that the student absentee problem is not confined to the U.S. or four-year private schools in upstate New York.

Everyone had a story to share and many wrote long posts with 5-7 analyses explaining the sources of the disengagement. Some had even more disturbing stories about only 25% of students attending week after week.

Photo by Kevin Casper.

Most contended attendance policies were meaningless and unenforceable in a climate that promotes self-care over collective engagement and where institutions obsess about retention and embrace a more bespoke way of dealing with students. One person wrote that he decided not to be a truant officer. Others asserted they would continue to grade based on their rubrics, knowing many students were likely to receive low marks or might not even pass.

I compiled the thoughtful analyses these professors shared as they tried to explain The Great Disengagement into an alphabetical list:

Adrift

Anomie

Anti-Intellectualism

Anxiety

Cell phones have ruined a generation

Cost of an education

Decline of interest in the humanities and critical thinking

Degree only to secure a job, anything else is useless

Diminished interest in intellectual life amongst students

Ennui

Expressing one’s own feelings is more important than abstract thinking or analysis

Film studies has less and less visibility in programs massively building up production courses

Films are too long and do not fit their new temporalities

Getting a job is more important than getting an education

Grade inflation is rampant, hard to do full spectrum grading

Greater divide between theory and practice in programs than ever before

Hard to chase down serial absentees

Isolation

Lack of curiosity

Lack of enthusiasm

Lack of experiencing campus life due to COVID

Lack of interest

Less and less interest in media studies courses and more fixations on production

Mental health crises that are pervasive

Narcissism

Neoliberal capitalism has altered the DNA of higher education where students are consumers

Non-interest in education itself, better to dream about jobs and making money

Pandemic was a huge disruptor

Pervasive anti-intellectualism across the globe

Poor engagement in everything except extracurriculars

Popular culture is revered and everything else denigrated as too hard or disturbing

Refusal to watch the films or do the readings

Screen studies courses do not equate directly with jobs

Self-care trumps everything now

Sitting and watching a film is considered a useless activity

Stress for students as they work jobs outside school

Students are lethargic about ideas

Students are actually 2-3 years younger in maturity due to the pandemic

Students are overwhelmed and overcommitted to extracurriculars deemed more important

Students no longer go to see any films, in theaters or on streamers

Students see intellectual challenge as an affront

Students see themselves as consumers and/or patients

Technophilia has replaced cinephilia

Trauma

Unable to cope with critical thinking and ideas that disrupt their own status quo

Withdrawal from collective experience and ideas

World is in total crisis with Ukraine war, climate catastrophe, economic collapse, political polarization

ABC

If you are an academic, you know the term ABD — All But Dissertation. But you might not know the term ABC — Anything But Classes.

About six or so years ago, I went out for post-teaching drinks at a local Ithaca dive bar with some early career colleagues after we finished our large lecture night class. We shared bags of salt and vinegar potato chips.

I casually mentioned that I noticed many students who were barely passing our exams had email signatures piled up with 5 or more titles from various extracurriculars: peer mentors, presidents of clubs, producers of a college tv show, resident assistants in the dorm, special groups to promote learning about the film industry, DJs, and crew members for a variety of productions unrelated to their own classes.

As a group, my colleagues chanted “ABC! You don’t know what ABC is?” I replied no.

They shared that graduate students everywhere know this term that refers to how colleges now promote everything but attending classes in their press releases, stories, speeches, and admissions events. They told me that the phenomenon is everywhere, not just at four-year private schools like the one I teach at.

One shared he had a drinking game he played with fellow early career faculty.

If they heard anyone such as an administrator, mid-level support staff, an area manager, or professor discuss courses, classes, teaching, faculty achievements, research, publications, or intellectual life in a public setting, they owed the others in their group a round of drinks.

This was before the pandemic ripped apart all that we used to know.

But these two stories twist together, students piling up extracurriculars at the expense of grades and colleges and universities pushing this new ideology of ABC to keep them on campus in order to fortify retention rates and fill dorm beds.

This new instrumental and neoliberal world presents a dystopian view of college without courses, classes without students, campuses without robust open public debate, departments without faculty. This scenario creates institutions without connections or urgencies beyond themselves, motoring a very problematic provincialism.

The new strain of long COVID is college without classes.

Collectivity and Intellectual Inquiry Are the Solution

In the 200-plus postings from my Facebook post where I openly shared my deep despair that 50% of my students skipped my class on the rise of radical independent media to expose the truth about the American War in Vietnam, many faculty offered solutions.

They refuse to submit to this new world where malaise and disengagement darken the soul of academia like black ink dripping from a broken gel pen. Many noted that this neoliberal corporate invasion needs to be fended off ferociously.

The most prevalent theme in their posts was simple and old school: faculty must get together on their own campus and on Zoom with others to share stories, diagnose the problem, analyze neoliberal academia, and take back higher education.

Poster for “Red Squad” (1972)

It reminded me of my students’ — the half who showed up — response to the anti-war films and new media we discussed. They were amazed to see groups of people protesting, arguing, analyzing, confronting, and fighting for something bigger than themselves.

They could not believe that these films had been shown in secret nighttime screenings at Ithaca College organized by students who discussed them until the early morning hours, not in a class or for a grade but simply to be part of a large political conversation beyond the campus. I reminded them that women did not have access to abortion, the men could be drafted and die in war, and racism was brutal. These movements converged. The stakes were high. The seven who showed up were enthralled, wanting to know more.

The call from faculty responding to my post seemed more linked to this tradition of collective sharing, struggle, and action than to succumbing to the disengagement malaise and paralysis.

Do It With Others

Faculty pointed out that many think they are alone as they endure The Great Disengagement, but this new era is global as well as political, soul-deadening, and dangerous. They contend the first step is to talk with each other about what we are all experiencing. We can’t devise any plans until we hear these stories. And we need to do this together.

One professor shared that their department met every two weeks to share stories about the massive disengagement, anti-intellectualism, anti-theory, and commercialism invading their campus like a kind of intellectual flu.

Photo on Hippopx.

Still, most who wrote publicly and privately said that their departments never held open discussions about these massive problems. Instead, across the globe, their centers for faculty pedagogy ran sessions on assigning less reading, instituting flexible deadlines, expunging lectures for student-run sessions, removing exams, and more.

Screen shot from “Off the Pig” (1968)

Many noted that being handed what are sometimes called “new pedagogical strategies” is simply neoliberal indoctrination that turns students into employees and/or consumers and faculty into a sales force. Spaces for robust honest discussion about student disengagement and what it feels like to be a professor enduring all of this seem few and far between.

It’s as though open discussion of these deeply disturbing scenarios is framed as an act of disloyalty.

Screen shot from “Red Squad” (1972)

Of course, it is disloyal to neoliberalism and disloyal to becoming a corporate training ground to produce obedient employees. Open, honest discussion about all our experiences and heartaches of The Great Disengagement would not only provide support, but might also help to devise imaginative solutions with others.

One person from another institution told me privately that their campus faculty center for teaching suggested all readings should be short and from popular culture so they are accessible — and should not exceed five pages a week! Most in the workshop resisted. They saw this tactic as a forced march into dumbing down classes and removing students from intellectual histories and traditions.

Abounaddara Collective site screen shot

Just two weeks ago after the semester ended, I had a powerful conversation after a meeting outside in the rare Ithaca sunshine with a science professor I had never met before. We ended up in an informal group of faculty from different disciplines discussing — what else? — the state of the college and students not attending classes. I shared how demoralizing it felt.

The professor recounted a story that stayed with me.

He described delivering a talk at another institution on his research. Formulas, ideas, words spilled into all the spaces on the white boards, students asked questions, faculty probed. It felt alive. It gave him hope.

Where has any sense of collective intellectual inquiry retreated to? Can we even discuss these two words in public anymore?

We are fighting a structural, systemic, and political problem, not bad pedagogy or lazy professors phoning it in or any one institution confronting its intensifying conundrums about what to do in this crisis. Higher education is in decline or collapse, morphing into something we might not recognize in five years.

We all want much more for our students.

As one Facebook poster pointed out, our identification and analysis of The Great Disengagement is not because we despise our students but because we care about their futures.

We want them to thrive in the messy world of ideas that disturb, unhinge, galvanize, provoke, entice, critique, prod, poke, deconstruct, and explode any and all assumptions.

And we want them to do it together and embodied and with us as their professors, not alone on their iPhones in their dorm rooms.

Patricia R. Zimmermann is the Charles A. Dana Professor of Screen Studies and Director of the Finger Lakes Environmental Film Festival at Ithaca College in Ithaca New York. The author or editor of ten books, her most recent are “Documentary Across Platforms: Reverse Engineering Media, Place, and Politics” (2019) and “Flash Flaherty: Tales from a Film Seminar” (2021). She is Editor-at-Large of The Edge.

Header image by Theonlysilentbob on Wikimedia Commons.