Natalia Almada’s documentary essay film “Users” (2021) questions a mother’s deep ambivalence about technology. But the film’s aesthetics makes clear that she has already chosen technology.

The film is the binational Mexican American director’s first shot in the United States and produced largely in English. The film opened at virtual film festivals such as Sundance, where Almada received the 2021 Documentary Directing Award and is currently in festival and theatrical release.

The film speaks clearly to our COVID moment, where reliance on technology has accelerated and social divisions have been exacerbated.

Recorded by the Kronos Quartet, the soundtrack works with the deft cinematography by Bennett Cerf, Almada’s brother-in-law, to slow time down. It creates space to meditate on and question technology and progress.

Almada’s film shuttles between the intimacy of family life and the vast technological infrastructure that sustains modern society. She bathes her child, lulls her baby to sleep in a vibrating smart crib, documents her son’s first steps. But the film also moves from the underwater network of fiberoptic cables to aerial views of water transported across an arid landscape.

The camera brings us into intimate and even invasive contact with her family. We view a baby nursing in close-up under the mother’s arm. As though positioned inside the computer’s screen, we watch a child play a video game. The camera then soars overhead. It offers sublime views from above that simultaneously inspire awe in the vastness of the technologically marked landscape and emphasize the camera’s omnipotence.

Nagging doubts of motherhood center her query. Can a human mother live up to the perfection our children learn from their technological minders? Almada created the film around this question, prompted by the Snoo smart crib. She asked herself “what would happen if I put my kid in there all the time and he fell in love with the Snoo instead of with me?” and built the film from there.

Yet despite mining such doubts, the film forecloses the answer. The camera tracks an airplane moving across the sky. It horizontally bisects the composition. She certainly can strive for and achieve such perfection. Her practice as an artist exemplifies this.

The minimal human role in the mechanized world constitutes one of the more disturbing themes in “Users.”

While Almada’s family takes center stage in scenes of leisure, the world of labor is machine dominated. We see a lone worker in layers of an underground greenhouse, the legs of a crane operator loading cargo. Until we get to the electronic waste recycling center, we do not see a human-centered workforce. Wearing protective gloves and filtration masks, workers sort and dismantle electronics.

This human heart of the film raises key questions.

What is humanity’s place in this technological future? How will technology exacerbate social divisions? Will we evolve into a world of those who benefit from technology and those who endure toxic working conditions to clean up after it?

Almada is not the first Mexican artist to pose such questions, but her approach is profoundly distinct.

Muralist Diego Rivera painted a technological epic, “Detroit Industry” (1932-1933), at the Detroit Institute of Arts, funded by the Ford family. His densely populated automotive factory proposed a future industrial utopia, where educated, thinking workers collaborate across racial boundaries.

In contrast, his colleague David Alfaro Siqueiros turned an electrical plant into a critique of capitalism in his collaboration at the Mexican Electricians’ Syndicate in Mexico City. His didactic approach in “Portrait of the Bourgeoisie” (1939-1940) warned that industry within the capitalist system destroys workers and generates fascism, war, and imperialism. Worker controlled industry, he argues, offers the only viable alternative.

“Users” offers no solutions.

Its minimalist use of humans within factories recalls Rivera’s Detroit contemporary Charles Sheeler. In Sheeler’s 1930s landscapes of the Ford factory, the rare human only draws our attention to the scale of the new U.S. picturesque, thoroughly technologically defined. Closer to Sheeler than the muralists, Almada neither preaches nor argues. Her priority is contemplation.

“Users” is a momento mori — a rumination on mortality.

From infertility technologies to an oilman’s heart transplant, our growing dependence on technology is clear. The visual pun connecting pumping oil rigs and the heart are intended. A wife works with a team of searchers to find her loved one’s ashes in the ruins of her house destroyed by the California wildfires.

Almada records her voice for a synthetic voice double. Will a future AI generated voice provide comfort to her children when she is gone? The result is disconcerting enough to suggest no. Yet as its sounds bleed into a more human-sounding version of our narrator, the boundary dissolves into ambiguity.

While the film revels in the unresolved, its own technological agility suggests that technology is here to stay.

One of the film’s final scenes makes this argument clear.

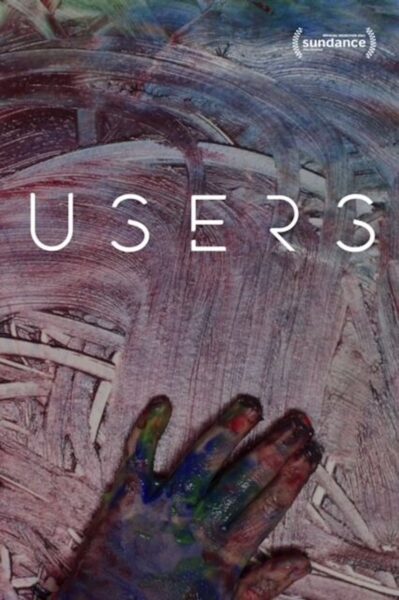

Almada’s son plays with fingerpaints. On the surface, this activity appears to be a nod to the pre-technological, a “hands on” activity for a child. The child begins to make side-by-side definitive circles, transforming the abstract smear of paint into an “owl.” Representation emerges from mere marks. This is the transformative moment when art becomes a technology, a tool of representation.

Throughout “Users,” the filmmaker’s highly technical art spotlights that Almada has already chosen technology. Technology allowed her to become a mother and a filmmaker.

What is less clear is whether we are ready to deal with the social and ethical implications of such choices.

While “Users” proffers an aesthetic of ambiguity and contemplation with its sparse narrative and unidentified landscapes, for some it might feel disingenuous, the product of intellectual melancholy. Yet a sense of technological inevitability remains.

Jennifer Jolly is the Charles A. Dana Professor of Art History at Ithaca College, where she teaches Latin American Art History, ancient through contemporary. She researches Mexican art and politics and has published essays on Mexican Muralism and technology in the Art Bulletin, the Oxford Art Journal, and elsewhere. The recipient of multiple Fulbright-García Robles Fellowships, she completed her prize-winning book, “Creating Pátzcuaro, Creating Mexico: Art, Tourism, and Nation Building under Lázaro Cárdenas” (2018), with the support of a National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship.