Floods wracked central Appalachia at the end of July, bringing national attention to the region. Much of the coverage has focused on the impacts of coal mining or fallen back on stereotypical representations of Appalachia and governmental responses.

The floods have been devastating for both residents and important cultural centers such as the Hindman Settlement School and Appalshop, founded in 1969 as part of federal poverty relief programs.

While the archives housed at Appalshop had never endured such devastation, floods are familiar topics to the media workshop. In 1975, Mimi Pickering released “Buffalo Creek Flood.” The film investigated the devastation caused by Pittston Company when its underbuilt infrastructure collapsed, causing 125 deaths and displacing at least 4,000 residents in the area.

Environmental collapse due to human intervention is not new to the region.

Anyone who has seen “Buffalo Creek Flood” will not forget the tearful recollection of the miner early in the film as he recounts seeing his neighbors’ houses washed down the river. The recent flooding was different, but not as much as some might assume. Systematic extraction of coal in the region left it vulnerable to environmental disasters and the recent flooding.

The images in “Buffalo Creek Flood” are horrifying but real: homes sink into the mud, wash down the valley with the flood, and pile up together like flotsam.

The recent flooding foregrounds another tradition of Appalachian environmental horror: the fantastic horror of the writer Nathan Ballingrud in “North American Lake Monsters” (2013) and “Wounds” (2019) as well as Steve Shell and Cam Collins through their narrative podcast “Old Gods of Appalachia” (2019-present). These examples illuminate a “Dark Appalachia,” where complex cultural histories connect with horrifying environments in order to reflect a regional perspective at odds with extractive industries.

Telling Ghost Stories

For these writers the horror genre transforms into a tool to explore the histories of Appalachia and their relationship with the oldest mountains in the United States exploited by companies from outside the region. With their complex interplay of unknowable wilderness and extractive industries, it is easy to distinguish home grown Appalachian horror from outsiders writing about Appalachia. Rather than a tale of good and evil, these works unfurl a complex, sometimes morally confusing, deep-rooted darkness in the histories of Appalachia. These works coalesce into Dark Appalachia.

In Ballingrud’s short story “Wild Acre,” developers on the Blue Ridge Parkway encounter a feral childlike creature on their construction site where forests have been cleared to make room for new suburbs. Rich in place-based language the writing captures the physical presence of Appalachia and its atmosphere: “Forest abuts the Wild Acre development site, crawling up the side of the Blue Ridge Mountains, hickory and maple hoarding darkness as the sky above them shades into deepening blue.” Ballingrud’s prose details the vision of the Blue Ridge region’s rolling mountains but also the feeling that inaccessible wilderness provokes.

Like many histories of industry in Appalachia, the cause of the horror is clear. But an ambivalence as to who’s to blame lurks. The clearing of the forests for the sake of profit summoned a “hostile intelligence,” the story’s term for the unexplainable monstrous force that emerges from the woods, but the lead contractor barely scrapes by and genuinely cares for his crew who are killed by the thing. Like many of the stories in “North American Lake Monsters,” in the end the horror has less to do with the actual manifestation of “monsters” than it does internal grief emerging from a working-class need for stability amidst the ruinous industries that supported their livelihoods for generations.

In the podcast “Old Gods of Appalachia,” scabs (strike-breaking workers) are brought in from the outside. When “Old Number 7,” the company mine, collapses, union boys enter the fiery pit to try to save who they can. The local boys know scabbing isn’t right, but the out-of-town miners are predominately African American. This tales acknowledges racist histories of coerced labor.

In the wake of the environmental disaster of the collapsing Old Number 7, those that perished in the mine rise as fiery ghouls. Their resurrection indicts how extractive capital intertwines with the ancient mountains, purported to have sealed away an ancient evil. In its third season, the narrative oscillates between explorations of the horrors lurking in the untouched wilderness and the industrial drives of humans to profit from it. The immediate perspective comes from those caught in the sway of these cosmic forces of ancient horrors and industry.

Extractive Industries vs. Local Solidarities

Films produced outside Appalachia depicting its horrors often miss these complexities of land and history.

“Spell” (2020) is a recent example of Appalachian folk-horror that repeats the tired tropes of “backwards” Appalachians casting ritualistic curses. The film repeatedly pits the protagonist from the city and his modern beliefs against the magic of the holler. It treats its subjects with disdain. With production companies in Los Angeles and London, “Spell,” shot in South Africa, constitutes a prime example of what the film industry dubs “runaway production,” seemingly place-based films shot elsewhere to save money.

Runaway productions like “Spell” portray those who inhabit Appalachia as the source of the horror. In contrast, home-grown Appalachian horror like the “Old Gods of Appalachia” podcast thread solidarity through the hills like ginseng diggers finding a rich patch of resistance. As the diggers teach us, there is no private property in Appalachia. The mining companies divvied up the land. They bought the “worthless mountain tops” for pennies on the dollar and then leveled with the most destructive mining practices available.

While “Old Gods of Appalachia” started as a podcast taking donations so that folks could listen for free, Shell and Collins have grown their listening community to support live shows hosted in Appalachia at Wise County High School (free for local students) and the Masonic Temple in Asheville, NC. After the first show in Asheville sold out quickly, they added a second. Serving as communal media, these live shows repeated lessons about who owns Appalachia with call and response and a radical inclusivity, adding to the familiar refrain of “welcome family” with “welcome our brothers, sisters, and our non-binary family.” The podcast website lists cultural collaborators, who work with the show to “create a world that is magical, scary, and authentically Appalachian, as well as respectful of BIPOC and LGBTQ+ folks.”

The shows involve local writers, musicians, and performers from Landon Blood performing the theme music to voice actors like Allison Puckett and Betsy Puckett. The original story told in the October 2022 live performance in Asheville reworked the performance of Johnson City, TN musician Jacob Danielsen-Moore’s performance of “Charcoal Suit.” These performances include the audiences that gather to acknowledge the real fears of the prison-industrial complex and the ways in which extractive industries have ground up communities. In “The Ties That Bind,” this extraction is depicted as the sacrifice of local workers to lay their bones down as rails, chaining their spirits to the railroad to be used by dark forces.

Runaway film productions like “Spell” are themselves extractive industry, mining place-based cultures and trading in images with no heed as to who they might harm. In contrast, local artists don’t need to concoct fantasies. Instead, they link atmosphere and feeling with histories. This dynamic process allows those who live in Appalachia to recognize and organize around the links between extractive industries, the Buffalo Creek flood, and the extreme weather events of these past months.

Horror in Environmental Documentary

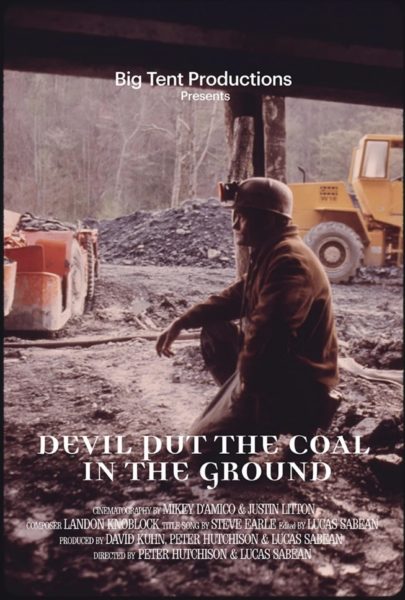

Contemporary documentaries focusing on the effects of the mining and energy industries on Appalachia such as “Cheshire, Ohio” (2014) and “Devil Put the Coal in the Ground” (2021) emphasize the devastation of communities whether from environmental degradation or the opioid epidemic.

These documentaries provide images of contemporary suffering in Appalachia that are not so unlike the fictionalized Appalachian horror of “Wounds” or “Old Gods of Appalachia.” The familiar haunted images of the empty town in Cheshire or the mother mourning her son lost to addiction lack the monsters of Appalachian Eco-Horror. Instead, they capture environmental devastation and death due to the systemic disavowal of the region, whether from mining companies like in “Devil Put the Coal in the Ground” or energy companies like in “Cheshire, Ohio.” As the latter film’s coda tells us, those that chose to remain in Cheshire when the energy company tried to buy them out in order to relocate them eventually succumbed to the slow violence of environmental toxins that permeate the town.

“North American Lake Monsters” and “Old Gods of Applachia” aren’t so different from “Buffalo Creek,” “Cheshire, Ohio,” or “Devil Put the Coal in the Ground” in their analysis of the socio-economic circumstances of the region.

The differing politics of these works revolve around questions of style and affect. The causes of slow violence in these documentaries might be hard to see. Although the violence of the monsters in Dark Appalachia is grotesque and visceral, their sources are often the same: mining companies, developers, companies that seek to exploit the inhabitants. Both offer ways for audiences to engage beyond “hill-people” stereotypes exemplified by mainstream media depictions in “Hillbilly Elegy” (book, 2016; film, 2020) or “Deliverance” (1972).

By inviting audiences to understand the complexities and long histories of the region, these books, podcasts, and films generate empathy. As Anna Creadick asks, “How can people identify with an Appalachia no one can see?” Local productions and local voices such as those from the Appalshop or the “Old Gods of Appalachia” podcast offer one way to push back on a region mired in dehumanizing stereotypes.

Those who have not experienced the generational trauma in the region will never know the pain of those who suffered from black lung, overdoses, or homes washed away in floods. But they might resonate with those metaphorical monsters that emerge from working-class entrapment in extractive industries.

Dark Appalachia is not just an empathy machine. While it might provide insight into regional environmental histories for those that have not experienced them, it is also a communal act of resistance. Dark Appalachia provides a way for those who live in the region to recognize the next phase of extraction as forests are cleared along the Blue Ridge Parkway or to understand the regularity of environmental destruction in the region.

These stories offer an opportunity to organize around a collective desire to protect Appalachia. The horror is real.

Matthew Holtmeier is Associate Professor and Co-Director of the Film and Media Studies Program at East Tennessee State University. He is author of “Contemporary Political Cinema.” He researches and writes on film-philosophy and environmental media, and his work has been published in Screen, Jump Cut, Film-Philosophy, Afterimage, Studies in the Humanities, The Journal of Chinese Cinemas, Middle East Journal of Culture and Communication, Journal for the Study of Nature, Religion, and Culture, Short Film Studies, and The Leonardo Electronic Almanac. He has also written for the Library of Congress National Film Registry.

Chelsea Wessels is Assistant Professor and Co-Director of the Film and Media Studies Program at East Tennessee State University. Her research interests include local cinema history and archives, global film genres, and feminist film. Her publications include writing for the National Film Registry as well as publications in Afterimage, Transformations, and Frames Cinema Journal.