We often discover new media fascinations in roundabout ways. In February of 2022, when filmmaker J.P. Sniadecki emailed me to ask if I’d seen Chloé Galibert-Laîné’s “Forensickness” (2022), I had only the vaguest sense of what had come to be called the “video essay.”

I was fascinated with “Forensickness” and was soon a devotee of Chloé Galibert-Laîné’s other video essays — in some measure because Chloé’s interests often overlapped with mine. “Reading//Binging//Benning” (2018, co-made with Kevin B. Lee) focuses on James Benning’s films, which I’ve often written about; “Reenacting the Future” (2018, also co-made with Kevin B. Lee) focuses on Peter Watkins, who I’d interviewed, written about, and for a time worked with; and “Watching The Pain of Others” (2019) explores “The Pain of Others” (2018) by Penny Lane, whose work I’ve followed for years.

I soon found my way to video essays by other well-known video essayists, including Kogonada’s “Eyes of Hitchcock” (2014) and Kevin B. Lee’s “The Spielberg Face” (2017), both of which I use regularly in my Introduction to the History and Theory of Cinema course.

In general, I’ve come to see the video essay as a new avant-garde, a range of meta-cinema experiences devoted to revealing and exploring the nature of cinema itself. I discuss this idea in an earlier essay for The Edge.

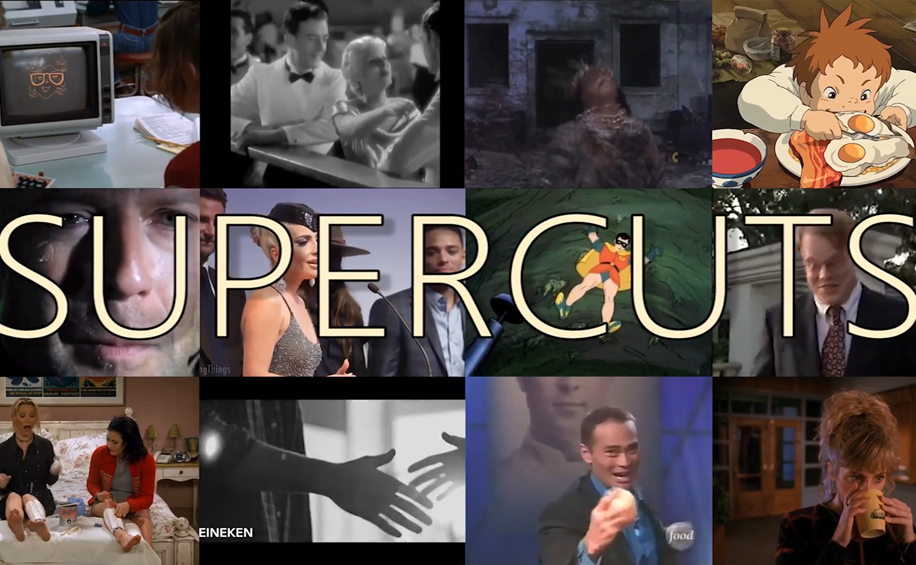

I quickly realized that some of the video essays I was seeing, including “The Spielberg Face” and “Eyes of Hitchcock,” were “supercuts” — another term then new to me. Andy Baio has been credited with “supercut” in 2008, defining it as a “genre of video meme, where some obsessive-compulsive superfan collects every phrase/action/cliche from an episode (or entire series) of their favorite show/film/game into a single massive video montage.”

The current Wikipedia definition reflects the recent growth of the supercut: “a genre of video editing consisting of a montage of short clips with the same theme. The theme may be an action, a scene, a word or phrase, an object, a gesture, or a cliché or trope.” Gradually, I realized that some of the films and film projects I’d long admired, and others that I’d recently come to admire, were closely related to the supercut.

There was, for example, Chuck Workman’s “Precious Images” (1986), produced for the Screen Actors Guild, which uses short clips from Hollywood films to illustrate and subtly question the various commercial genres of American pop cinema.

Another excitement, one my then-student Ava Witonsky brought to my attention, was Jennifer West’s “Film Title Poem” (2016). West set out to remember and to the extent possible revisit every film she recalled seeing, from childhood until 2016, in order to discover what memory had retained and what it had distorted. West (and her collaborator Peter West) filmed the title cards for each film she revisited, and placed them in an overall alphabetical structure. (West has made “Film Title Poem” accessible in full here with password “lighter.”)

West marks each transition from one letter to the next with an in-frame collage made up of several title cards; also, from time to time, she riffs for a cinematic moment on an individual title or an individual word from a title, before returning to her overall alphabetical organization. Here’s the listing for the letter E, with West’s brief riff on “Enter”:

E.T.

Easy Rider

El Mariachi

Elephant

Enter the Dragon

Enter the Void

Mask//Enter//Liquid Sky//Enter//28 Days Later//Enter//Yellow Submarine//Enter//

Eraserhead

eXistenZ

Throughout “Film Title Poem” the visuals are accompanied by clips of sound from a wide range of remembered films. Also, animators Kelsey Boncato and Sadie Marchese-Moore worked with West to add imagery directly to each title card, scratches and painted imagery that reference some aspect of the film.

What I found particularly exciting about “Film Title Poem” was the breadth of West’s cinematic awareness. She includes title cards of well-known and often canonical Hollywood films (“Vertigo,” “Godfather II,” “The Conversation,” “After Hours”…), foreign-language features (“Jules and Jim,” “Weekend,” “Red Desert,” “8½,” “Solaris”…), lower-budget independent features (“Shadows,” “Chan Is Missing,” “Daughters of the Dust,” “Wendy and Lucy,” “Deep Throat”…) and a wide range of documentaries (“Don’t Look Back,” “Punishment Park,” “When We Were Kings,” “CITIZENFOUR”…), plus early films only a film historian or a cinephile would be likely to know (Edwin Porter’s “Dream of a Rarebit Fiend,“ Lois Weber’s “Suspense”; “The Life and Death of 9413,” co-directed by Robert Florey and Slavko Vorkapić…) and films identified with the 1960s/1970s/1980s avant-garde: Brakhage’s “Mothlight,” Hollis Frampton’s “Lemon,” Chantal Akerman’s “News from Home,” Mulvey and Wollen’s “Riddles of the Sphinx,” Barbara Hammer’s “Dyketactics,” Jack Smith’s “Flaming Creatures,” and Bruce Conner’s “A Movie” — a particularly crucial influence on “Film Title Poem,” often alluded to during the film, sometimes with just “A.”

The final film reference, seen only once during “Film Title Poem,” is to Frampton’s “Zorns Lemma” — a seemingly inevitable conclusion to West’s alphabetic listing, since “Film Title Poem” echoes Frampton’s use of the alphabet both as a structuring device and as a way of creating suspense. Just as we wait impatiently for the final substitution image in the long middle section of “Zorns Lemma,” we wait, during West’s riffs, to return to the ongoing alphabetic ordering — and more generally, for “Film Title Poem” to conclude. “Are we only at L?!”

Gradually I found my way to other epic compilation films that resemble supercuts. There’s the 86-minute Hungarian feature, “Final Cut: Ladies & Gentlemen” (“Hölgyeim és Uraim,” 2012) by Pálfi György, which is essentially an expansion of Workman’s “Precious Images” — in this case focusing on romantic melodrama throughout the history of global commercial feature films.

Each cut in “Final Cut” moves the imagery from one film to another. Hundreds of films are referenced within an overall picaresque narrative structure, regularly interrupted by moments of supercutting. We also recognize that some films are included more than once, creating a mini narrative within György’s meta-narrative. The visual and sound editing in “Final Cut” is engaging, often witty, sometimes moving. The film can be enjoyed as a feature or one can choose to watch a random montage:

There is also Jason Mittell’s 4:45-minute compilation, “Object Oriented,” the Coda to the 20+ sections of his open-access “video book,” “The Chemistry of Character in Breaking Bad” (2024). In quick succession, we see significant physical objects from each episode of the five-season series — beginning with Walter White’s flying pants from season one, episode one.

According to the credits, “Object Oriented” includes “all ‘Breaking Bad’ shots lasting at least one second where non-vehicular objects appear centrally without any human/animal presence in the frame; arranged in chronological order; time remapped to match musical rhythm.” While “Object Oriented” is relatively brief, fully understanding its implications would require careful exploration of all 62 episodes of “Breaking Bad.”

When I originally googled “supercut” to find a definition, I noticed that “A Supercut of Supercuts” (2021) was also listed, and when I finally accessed Max Tohline’s 131-minute epic, I was astonished. Here was not simply a new contribution to what was coming to seem a tradition of supercutting, but a compendium of supercuts by others and by Tohline himself, all arranged within a detailed exploration of an aesthetic context for the supercut, a thorough review of its history, and Tohline’s sense of the form’s ideological underpinnings and cultural implications.

In his introduction to “A Supercut,” Tohline argues that “supercuts embody a new mass approach to visual history” and explains that his central concern is the rise of “database thinking” — before providing an outline of the three chapters to follow. Tohline provides his own definition of “supercut”: “A briskly cut video list of appropriated moving images sharing some specific matching characteristics and offered as a representative cross-section of that characteristic.”

The first chapter, “Aesthetics” (22.5 minutes), focuses on the distinction between narrative continuity (syntagmatic structures), where editing provides the visual and sonic clues that allow us to follow a narrative; and paradigmatic structures, sequences of images in which particular visual/sonic/conceptual elements of the selected images provide a recognizable, non-narrative continuity. This non-narrative continuity, Tohline explains, can be focused on pleasure or on analysis.

In “Histories” (51 minutes), Tohline’s focus is two-fold. First, he debunks the common assumption that one or another moving-image artist — Joseph Cornell, Bruce Conner, Dana Birnbaum, Carl Reiner, Candy Fong (an early maker of “fanvids,” or fan videos), and Christian Marclay — is the founder of the supercut.

Second, Tohline argues that the supercut is not a contribution of one or another particular strand of cinema history — avant-garde film, video art, commercial cinema, fan video — by providing an expansive exploration of the relevant cinema history and pre-history. He also surveys other aspects of cultural production — photo-collage, gallery installation — that have predicted and helped to create the modern context within which the supercut, one particular form of compilation film among others, has evolved.

In “Databases” (50 minutes), Tohline explores the interplay between technology and ideology within the evolution of the modern supercut’s “database logic.” Basically, he sees the supercut as a crucial instance of the gradual replacement of a culture-wide “archival impulse” by a “database impulse.” The digitalization of traditional cinema, along with the recording and storing of data from many day-to-day aspects of contemporary life, has resulted in a transformation in how we understand and use audiovisual media, as well as more generally, in how we see the world and how we are re-structuring our lives to cope with this ongoing transformation.

As Tohline’s title suggests, “A Supercut of Supercuts” is a meta-supercut. It combines a plethora of individual supercuts in the way that individual supercuts combine clips. And it uses “brisk” cutting throughout, often asking us to comprehend multiple moving-image screens, each of which is revealing particular repeated elements, within his larger frame.

Tohline has created an audiovisual work that is simultaneously a fascinating, engaging, dense and comprehensive work of audiovisual scholarship and a creative masterwork that makes the history of modern media not just more understandable, but on many levels, available. The array of supercuts excerpted within “A Supercut of Supercuts” is itself useful. Video essays usually provide an end-credit listing of sources of clips, but Tohline also provides the information necessary for accessing an extremely wide range of supercuts and other, related forms of media art, as well as of writing about this history.

(Thanks to Jeremy Lovelett for his patient technical assistance; and to Patricia R. Zimmermann, who originally brought me to The Edge and whose sudden passing, this past August, has left her many collaborators and friends in mourning.)

Scott MacDonald is author of “A Critical Cinema: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers” (5 volumes, California), “The Garden in the Machine” (California, 2001), and 14 other books, most recently “Avant-Doc: Intersections of Documentary and Avant-Garde Cinema” (Oxford, 2015); “The Sublimity of Document: Cinema as Diorama” (Avant-Doc 2) (Oxford, 2019); “William Greaves: Filmmaking as Mission” (with Jacqueline Stewart; Columbia, 2020) and “Comprehending Cinema” (Avant-Doc 3) (forthcoming). Named an Academy Scholar by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in 2011, he teaches film history and programs F.I.L.M. at Hamilton College.