South Butler, New York, is a forgotten byway in American history.

Its moment of notoriety came and went.

Now it is just a crossroad hamlet struggling to matter like so many other such places in rural America. But once it did matter.

In the decades before the Civil War, South Butler featured a Congregational Church that drew major figures in the socially progressive movements of the day — abolition, women’s rights, temperance. South Butler’s Congregational Church distinguished itself by calling to its pulpit the first African American ordained in a mainstream Protestant church, Samuel Ringgold Ward, and the first woman so ordained, Antoinette Brown (later Antoinette Blackwell).

The South Butler Church

The South Butler church drew other prominent figures in the abolition movement.

Gerrit Smith spoke from the South Butler pulpit during the service in which Antoinette Brown Blackwell was installed as pastor. In 1845, Lewis C. Lockwood was appointed to replace Samuel Ward, who had taken ill and moved to Geneva, New York, to convalesce.

Lockwood would go on to found schools throughout the south devoted to educating formerly enslaved African Americans. Lockwood is little remembered today. In addition to his work on behalf of abolition and on improving the lives of the formerly enslaved, he transcribed hymns and songs he heard among the African Americans with whom he worked, including one that became very famous.

According to the December 2, 1861, New York Daily Tribune, Lockwood traveled to Fort Monroe, a Union fort in Hampton, Virginia, to minister to escaped slaves whom the government designated “contraband.” As the Tribune explained:

“In winter 1861, the American Missionary Association sent Rev. Lewis C. Lockwood to minister to former slaves who had sought sanctuary at the Union-run Fort. While working at the “Grand Contraband Camp,” Lockwood transcribed the words to the following spiritual.

A Song of the Contrabands

O let us on to Canaan go, O let my people go!

What a beautiful morning that will be! O let my people go!

When time breaks up in eternity, O let my people go!”

The hymn is now better known as “Go Down, Moses.”

We can imagine what drew Lockwood to the task of transcribing this hymn — he recognized the biblical allusions in the song. The enslaved Africans were analogous to the enslaved Israelites of Exodus. Throughout the abolitionist labor in antebellum Wayne County, New York, we find echoes of the Bible authorizing the effort.

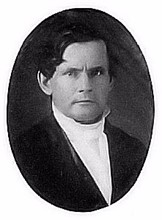

Lewis C. Lockwood

Wanderings

As I think back over the research I conducted for these essays for The Edge and for the larger work from which they are drawn, I am struck by the wandering way I went about it.

I spent a great deal of time driving from our Ithaca home to various libraries and archives in a triangle of Upstate New York: from Ithaca to Rochester and then east toward Syracuse. I spent time in archives and church basements and county history archives. I did longer trips to New York City and Philadelphia, where some of the original church records from the Burned-Over District are housed.

While working the Upstate triangle, I would drive as directly as possible in the morning, following as closely as I could how the crow might fly from Ithaca to Rochester or to Lyons, New York.

After I’d spent hours in the particular archive I would drive home following what my grandfather would have called “the cross-lots route.”

For instance, I would leave the Colgate Rochester Crozier Divinity School library and, instead of getting on the interstate highways system, I would head toward Monroe Avenue in Rochester and turn east on it. Monroe Avenue is New York State Route 31. It generally runs parallel to the old Erie Canal, through the port villages of Pittsford, Fairport, Macedon, Palmyra and on east.

The original Erie Canal just east of Lyons, New York. This portion of the original canal was abandoned sometime in the later antebellum period and has been filled by decades of disuse.

Opened in 1825, the original canal was four feet deep and 40 feet wide. Expansion that was begun in 1835 and completed in 1862 rerouted some of the canal. Eventually New York State remade the canal into what is now known as the Barge Canal.

The Barge Canal, west of Lyons, New York.

Spreading the Ashes

Many of these villages along the canal figure prominently in the ferment of the antebellum period.

A few miles south of Palmyra, Joseph Smith and his family settled in the year of “Eighteen Hundred and Froze to Death” as 1816-17 was known, owing to a canopy of volcanic ash that covered the globe. It caused widespread crop failures in the “Northern Kingdom” of Vermont, driving hundreds of farming families off the unforgiving land there toward the newly opened western frontier of Upstate New York.

Smith’s family were among the “westering Yankees” in those years, as were a wing of my maternal ancestral family. As young Joseph dug in a glacial drumlin, later named the Hill Cumorah, on his family’s farm, he found the golden tablets that gave birth to Mormonism.

Hill Cumorah

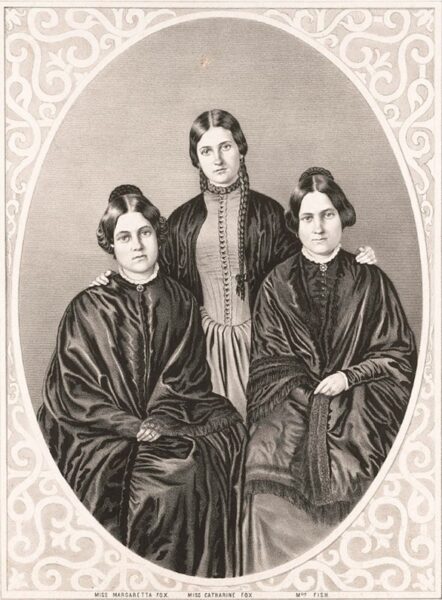

A bit farther east, 31 passes through Newark, New York, where, in 1848, the three young Fox sisters reported they’d learned the trick of interpreting strange tapping noises as communications from the spirits of the departed. And even though one of the sisters later admitted it was all a hoax, their table-rapping spawned an international phenomenon called Spiritualism.

The Fox Sisters

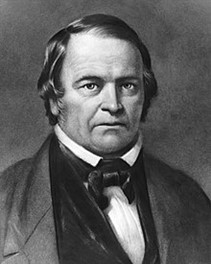

Throughout the Rochester hinterlands north and south of the Erie Canal, Millerism spread in 1843 and 1844. This is the widespread faith in the prophecies of a self-taught farmer, William Miller, who declared that the world would end, and Christ return at some point. First, he predicted, in 1843 and, when that did not come to pass, more precisely in October of 1844.

Among the lingering effects of Miller’s work is the Seventh Day Adventist church, an offshoot of which became the Branch Davidians who under the leadership of David Koresh figured in one of the signal catastrophes of the Clinton administration outside Waco, Texas.

The overwhelming disappointment following the failures of Miller’s prophecies to come to fruition much later led a social psychologist, Leon Festinger, and his colleagues, in a book called “When Prophecy Fails,” to coin the term “cognitive dissonance,” the psychological dislocation that occurs when reality does not correspond to the ideological constructions through which one’s mind perceives the world.

William Miller

Burying the Ashes

Many of these post-archival wanderings had family connections for me. My research-laced searching for answers to private questions of family matters with more broadly historical and sociological questions of antebellum activism. Among the sites I would search for were the cemeteries where my ancestors are buried.

It dawned on me as I catalogued those cemeteries and graves — Evergreen Cemetery in North Huron, Lakeside in Wolcott, South Butler-Savannah in South Butler, Tallman out in the fields between South Butler and Weedsport — that my ancestors stayed while Samuel Ringgold Ward, Antionette Brown, Gerrit Smith, Lewis Lockwood and so many other of the activist reformers did not.

Zenas Stone’s daughter, Maretta, raised her son, Willis, in South Butler. Willis eventually moved five or so miles from South Butler to his wife’s family’s farm where they raised their four children, three sons and a daughter. One son moved to Michigan, the rest of the children remained in eastern Wayne County, including my grandfather who remained for the rest of his life on the farm he inherited from Willis and his wife, Viola.

Born and raised on that farm, my mother married and moved with my father to the New York City suburbs where they raised my sister and me. And now here I am, back in the Burned-Over District raking over the ashes of which, when once they were flaming, my ancestors must have felt the heat.

In 1984 in the Evergreen Cemetery in North Huron I found the grave of my great, great, great, great grandfather, Elihu Jones. He was born in Coventry, Connecticut on April 25, 1751. He died in 1828 in Huron, New York, in Wayne County. Huron is adjacent to Wolcott and South Butler.

He served in the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War and secured a large parcel of land in what came to be called the Military Tract in exchange for his service. This was land that was confiscated from the Haudenosaunee.

The land that Jones and Stone and my other ancestors settled upon is in Wayne County. The only consolation available to me is that what is now Wayne County was mostly uninhabited by the Haudenosaunee people because it was reserved as hunting grounds.

When I first came upon Elihu’s grave in 1984, the stone was firm and upright and clearly legible. Engraved upon it were his name, his dates, and this verse:

Reflect my friend when passing by,

As you are now, so once was I.

As I am now, so you must be.

Prepare for death and follow me.

I confess: I have never really gotten over this blunt, dare I say rude, grab of my sleeve from beyond the grave. Who writes something like this, I found myself asking.

The verses are typical of the era and appear throughout the northeastern United States. I could not help myself from asking about the sort of person who would have those words incised in stone for posterity. Who would leave this for his descendants to muse over?

I did not take a picture of the grave. Years rolled on.

I returned to the Evergreen Cemetery last year and found that Elihu’s gravestone has partially collapsed. It has split. Someone has wound a steel wire around the stone to keep the upper and lower halves of it somewhat intact. The engraved writing along with his name and dates are almost completely erased.

The Legacy of the Burned-Over District

What we call the Burned-Over District was limited in both space and time.

It is clear that those flames did gutter and fade. Samuel Ward eventually fled the U.S., first for Canada, then England, and finally settling in Jamaica where he died in 1866. He lived to see slavery abolished but of course the profoundly catastrophic effects of slavery and the racism it both engendered and perpetuated have never been fully overcome. Gerrit Smith lived long enough to see abolition win out, dying in 1874.

Antoinette Brown Blackwell had a long career as an activist and speaker on behalf of abolition, temperance, women’s rights, and other socially progressive causes, all of which she did well away from South Butler, New York. She was able to balance her intellectual labors with marriage and the raising of a family, despite the rigid domestic roles the prevailing gender ideology imposed.

According to Elizabeth Cazden’s 1983 biography, Antoinette wrote in 1874, reflecting on the “separate spheres”:

“Wife and husband could be mutual helpers with admirable effect. Let her take his place in garden or field or workshop an hour or two daily, learning to breathe more strongly and exercising a fresh set of muscles in soul and body. To him baby-tending and bread-making would be most humanizing in their influence, all parties gaining an assured benefit.”

Ironically, during the ceremony marking her ordination as pastor of the South Butler church, a powerful thunderstorm threatened to upend the festivities. The storm prompted Gerrit Smith to pen two satirical quatrains playing both on the ideology of the separate spheres and the unique sight of a woman being installed in a mainstream church:

This pouring rain doth make it clear,

That silly woman must not teach;

When will you learn, my sister dear,

That noble man alone should preach?

So now, Miss Brown, just stay at home,

Tend babies, knit, and sew, and cook;

And, then, some nice young man will come

And on you cast a loving look.

Just as she was rising to take the pulpit, Smith passed these stanzas to her.

Antoinette lived to see the 19th amendment ratified and to vote in her first and only presidential election in 1920. She died on November 5, 1921, in Elizabeth, New Jersey.

Ideological Madness and Magic

Nonetheless, it is sobering to consider if over a century and a half after the fires that swept through South Butler we have come very far. Perhaps we have progressed beyond the ideological madness that provoked some of Ward’s bitterest condemnations of the people of the United States. Ward wrote in “Autobiography of a Fugitive Negro” in 1855:

“one almost regards ‘American’ and ‘Negro-hater’ as synonymous terms … Surely it is with no pleasure that I say, from experience, from deep-wrought conviction, that the oppression and the maltreatment of the hapless descendant of Africa is not merely an ugly excrescence upon American religion — not a blot upon it, not even an anomaly, a contradiction, and an admitted imperfection, a deplored weakness — a lamented form of indwelling, an easily besetting sin; no, it is part and parcel of it, a cardinal principle, a sine qua non, a cherished defended keystone, a corner-stone, of American faith — all the more so as it enters into practice, the everyday practice, of an overwhelming majority …”

The current panic over “white replacement theory,” and critical race theory; the panic over transgender people; the widespread and clearly racist attack on voting rights; and all the issues that drive ideological divides ever deeper are now visible in the very Burned-Over District that once was so hospitable to progressive social causes like abolition and women’s rights.

A sign in a yard on the Savannah-South Butler Road.

Given the venom, I find myself looking back to those equally divisive decades before the Civil War, looking back to the tiny village of South Butler and wondering if we could find some of that magic again, some of what prompted Samuel Ward and Antoinette Brown to find reasons for hope there. As Ward put it in his autobiography,

“[South Butler] people were honest, straightforward, God-fearing descendants of New England Puritans. Living in the interior of the State, apart from the allurements and deceptions of fashion, they felt at liberty to hear, judge, and determine for themselves, and to act in accordance with what the Bible, as they understood it, demanded of them.”

Ward celebrated what he felt to be the signal difference between South Butler and most of the rest of the United States:

“The manly courage they showed, in calling and sustaining and honouring as their pastor a black man, in that day, in spite of the too general Negro-hate everywhere rife (and as professedly pious as rife) around them, exposing them as it did to the taunts, scoffs, jeers, and abuse of too many who wore the cloak of Christianity–entitled them to what they will ever receive, my warmest thanks and kindest love.”

Compare that with Antoinette’s comment on South Butler in a November 1854 edition of the New York Daily Tribune:

“South Butler is a little village noted for its variety of religious views and denominations, and for its independent canvassing of all mooted opinions. As a retired spot for an inexperienced preacher to do good and get good, to think carefully and speak freely, it has fully met my expectations.”

Samuel Ringgold Ward, Antoinette Brown Blackwell, L. C. Lockwood, Gerrit Smith are people whose lives and work left a light that still shines, however dimly, in the Burned-Over District.

David DeVries retired from Cornell University where he served as associate dean for undergraduate education in the College of Arts and Sciences. He has a life-long fascination with the Finger Lakes and western New York, particularly its nineteenth century history as the so-called “Burned-Over District.” This fascination stems partly from the fact that his mother’s family had settled in South Butler and the Wolcott area in the first decade of the nineteenth century. This piece is adapted from a longer work entitled “Reading the Slates,” a cultural memoir.