On Friday, June 24, in a 6-3 decision, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade. This day also marks exactly four months of fighting in Ukraine. Both are wars, entangled and unsettled.

These conjunctions offer a way to fashion a mosaic of connections, rather than considering events in isolation. Contiguities, where the near and the far, the personal and the political, the micro and the macro, the historical and contemporary connect are now essential.

Headlines from Variety, Deadline Hollywood, the New York Times, and the Washington Post stacked up in my email, an ostinato of right-wing conservatism.

My friend Zillah Eisenstein texted me at 10:43 a.m. She wrote “I am weeping, fuck the court.”

Jane Shattuc, my closest friend from graduate school, texted me at 11:11 a.m.: “OH noooo!” She shared “I am at Consoling Passions and people are crying.” Consoling Passions is the conference for feminist media scholars, meeting in Orlando Florida for the first time in person since COVID.

The text and emails catapulted me into another dimension of fear, anger, shock, and rage followed by an icy realization that my life had just changed. I would be in the streets again.

Arias

I could not absorb the news anymore. Not alone. I needed fortification, and it felt imperative to hear women.

I grabbed my iPhone, scrolled to Apple Music, and typed in soprano arias. I needed opera, music that exceeds the words it merges with notes, brought by female voices pulling us past the earth to see more clearly what lies below.

Aria means air. In operas, the aria moves away from the action, a meditative soliloquy.

The first aria on my playlist was “Dido’s Lament,” from Henry Purcell’s Baroque opera “Dido and Aeneas” (1688). The words are “When I am laid, am laid in earth, Remember me! Remember Me, but ah, Forget my fate.” Listening just minutes after the court overturned Roe v Wade, where Dido expresses her grief that Aeneas has abandoned her, I am struck by the way that the U.S. has abandoned women and those who give birth today. It is no longer my country.

And then, from Variety, a story arrived in my email: the singer Phoebe Bridges summoned the audience to join her in a chant “Fuck the Supreme Court” at the Glastonbury Music Festival in the UK.

A breeze whooshed through the screens of my enclosed porch, and suddenly, I remembered Cindy. She was a close friend from my all-girls Catholic high school, Immaculate Heart of Mary in Westchester, Illinois, in the suburbs of Chicago, and I had not thought about her for decades.

Cindy was the first person I knew who had a boyfriend and the first of my friends to have sex. Her boyfriend was eight-years older, exotic to all of us, an adult with a mysterious job and a pick-up truck. Weeks after they met, she was pregnant. In those pre-Roe v. Wade days, she flew to New York state to have an abortion.

Just two weeks before the Supreme Court decision, I had watched the HBO Max documentary film The Janes (Tia Lessin and Emma Pildes, 2022), the story of the radical women’s collective in Chicago pre-Roe v. Wade who performed abortions for poor women who could not afford to fly to New York.

The film features interviews with members of Jane, the code name used for the phone line for women to set up appointments for abortion. They share details of how they did this work underground as a collective and how they supported the women who called. They learned how to administer abortions. Some were arrested. The documentary shimmers with archival news and amateur footage showing connections between the anti-war, civil rights, and feminist movements in the late 1960s and early 1970s. We see images of women protesting in the streets of downtown Chicago.

In high school, I did not know that only a twenty-minute drive from my family home on Essex Street in Westchester, radical women broke the law to provide affordable illegal abortions to those without funds to fly to New York state.

Ice Breakers

At IHM as we called it, none of us thought much about boys, boyfriends, dating, or sex. Instead, we drowned ourselves in Anais Nin and Emily Dickinson and Nadine Gordimer, worlds away from Catholic nuns.

We fantasized exiting the suburbs for college far away from the ordered streets, expansive green parks, and nuns in habits so we could go to feminist and anti-war demonstrations. To bide our time, we sewed secret inside pockets into our blue uniform blazers to hide the joints we smoked in the confessionals in the chapel when the nuns ordered us to go and engage in meditative prayer about the Virgin Mary.

Writing this now, I am stunned that marijuana might eventually be legal in more states than abortion is.

In my second year, a mobile van pulled up in the high school’s back parking lot, hidden from busy Cermak Road in front. The Chicago-area Catholic pro-lifers had filled the van with fifteen fetuses in various stages of development, floating in formaldehyde-filled glass jars like aliens in a science fiction film.

The nuns exempted us from our mandatory daily Catholic religion class to march single file through the van to view the fetuses. We could take as much time as we wanted, but we all just wanted to get out of there. Inside, an older woman with orange lipstick and hair ratted in a beehive warned us to not to have sex. She said these “little babies” possessed special souls that shimmered brightly with God’s love. We were repulsed.

Just eight months after the passage of Roe V. Wade on January 22, 1973, I started at the University of Iowa. Meanwhile, the war in Vietnam wore on.

At orientation, the senior who was my group leader pulled all the women students aside for an ice breaker exercise. She told us she was instructed to help us get to know each other and then encourage us to study in the library, directives she assessed as infantilizing, patriarchal, and useless.

Instead, she disclosed with great insistence that the university’s student health services dispensed contraceptive pills and that abortions could be accessed in Iowa City. It was a new era for women, she argued — and we were the first class to have this access. We had choice.

Then, three weeks later, on September 12, 1973, I found myself at a demonstration outside the three-story white windowless AT&T building protesting the U.S.-supported coup overthrowing Salvador Allende in Chile the day before. Friends from the dorm insisted I go with them, but I knew nothing about Chile, Allende, or U.S.-backed coups.

Graduate students were wearing black armbands. In Chicago, I had only seen armbands at Irish Catholic funerals for deceased uncles from Scotland and Ireland I barely knew. These older students offered dense, impassioned theoretical analysis of U.S. imperialism, hegemony, ideological warfare, and solidarity with Latin America. Their waterfall of intimidating, impenetrable jargon baffled and alienated me.

But their passion for ideas and politics made me feel I had crossed over into a world where analysis and not religion motivated collective action.

Cindy, Vietnam, and the Nuns

Smart, beautiful, funny, Cindy loved art. She drew on notebooks, napkins, cardboard, and even our forearms. She was a lioness, ferocious about art, her friends, and her boyfriend.

In 1972, I was editor of the high school newspaper while the Vietnam War (called the American War by Southeast Asians) jammed the TV news. My paper covered stories about our volleyball team, food drives for the needy, and car washes to raise money for field trips to the Art Institute of Chicago.

That Spring, with anti-war demonstrations everywhere and news of the Black Panthers infusing the Chicago evening TV news, we finally ran a story on the protests. Some students had older brothers or cousins who had been drafted and were fighting in Vietnam.

Two weeks before, I ended up at a rock concert at a working-class high school gym featuring an unbearably loud off-key psychedelic band. Some of my girlfriends were tripping on LSD.

I met a boy named Jerry, mostly because he, like me, was not tripping. His parents knew the parents of one of my school friends. A senior, he had enlisted in the Army that same morning and was excited to go fight in Vietnam after graduation. I had never met anyone who joined the army. First, I was at an all-girls school. Second, I was middle class. Everyone I knew was focused on college and SATs.

Some of the younger nuns at IHM spoke to us in secret after school about Father James Groppi, the Milwaukee civil rights and fair housing movement activist priest who led marches against the war. They worshiped him as though he was the lead singer of The Rolling Stones or Jesus Christ himself.

Furtively, these nuns told us that they were against the war.

After an English class where we dissected “Romeo and Juliet,” one nun insisted that because many Vietnamese were Catholics converted by French colonizers, we should support their struggles. My girlfriends and I laughed that the nuns loved the play because both lovers died in the end before they could have sex. But we loved that this nun shared her secret support for the Vietnamese with us.

The Pieta

At the student newspaper, we decided to protest the war. We did not want to wait until college.

Cindy drew an image of the “Pieta,” Michelangelo’s 1498-1499 sculpture, with the Virgin Mary cradling a dead bloodied U.S. soldier across her lap instead of Jesus Christ. Plastic and stone miniatures of the “Pieta” peppered shelves in friends’ homes, a revered Catholic icon of women taking care of men. I wrote a short piece about why Catholic high school girls needed to protest the war.

In those ancient pre-digital days, we adjusted type and headlines by hand, cutting them out with small sharp scissors and then gluing them to the mock-up pages. I took Cindy’s hand-drawn black ink image and pasted it on the front page. It needed more rubber cement swabs than the small words I moved around.

Five minutes later the nun in charge checked the galleys before they shipped out to the printer. She shrieked that this image could not be printed: it was blasphemous to the Catholic Church, an act of desecration, a mortal sin against the Virgin.

She locked me in the newsroom. She would not release me until I cut out the image.

Then she called my father.

I argued with her about my rights to free speech and the war. I screamed that the nuns who taught us physics and art history and English were anti-war and venerated Father Groppi.

Two hours later my father arrived in his grey business suit and blue striped tie, back from his commute to his executive job at Sears Roebuck on the west side of the city. He refused to support the nuns and their claims of desecration. To their horror, he defended me.

He informed the nuns that there was freedom of the press even in a Catholic girls’ school, and that no nun, Virgin Mary, or even Jesus Christ himself was above the law. He asserted he was taking me home because he did not want me imprisoned by anti-free speech nuns. He demanded they print the paper. He said he did not believe in desecration. He believed in debate.

The next day, the paper was published.

Within an hour, not one copy could be found. At first we thought the nuns stole the copies in a further attempt at censorship. Instead, the IHM students had grabbed them to share with friends at other suburban all- girls Catholic schools.

Basement Screenings

At Iowa I majored in English, obsessed with writing poetry and reading obscure 19th century novels. That demonstration to support Chile had opened me up to the poetry of Pablo Neruda and late-night film screenings at the Bijou Cinema on campus after studying in the library.

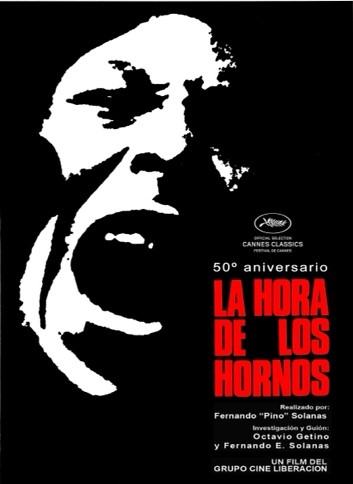

It also lured me into underground screenings in the basements of university buildings hijacked by activists late at night, where I saw radical political documentaries such as “La hora de los hornos” (“The Hour of the Furnaces,” Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino, Argentina, 1966-1968), about neo-imperialism and social struggle, and “When the People Awake” (Anonymous, Chile, 1972-1973), a film chronicling Chile’s transition from capitalism to socialism.

We crammed into the classrooms and sprawled on the floor. These activist events featured both screenings and intense audience discussions about the politics of the film and actions we needed to take.

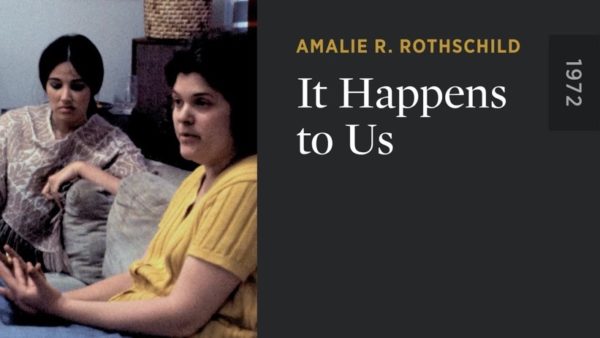

Some sorority girls I knew from my first year in the dorm induced me to attend feminist screenings in these same squatted spaces.

I saw films like Julia Reichert’s “Growing up Female” (1971), Amalie Rothschild’s “It Happens to Us” (1972), about illegal abortions, and “Abortion and Women’s Rights” (1970) where women told their stories. Sorority girls, hippies, tennis players, druggies, nursing students, chemistry grad students, women from the famed Writers’ Workshop, and militant feminist activists fired up rousing debates about women’s rights and abortion, and how we all, together, needed to fight the patriarchy and smash it down to dust.

The intensities were thick, complicated, and remained unresolved. Remarkably, what was secret in high school flourished out in the open among these women, even if underground in the basement of the social science building. I decided to double major in English and Film. It seemed that the most radical women were students in the film and tv major, and I liked their intensities.

Unlike my students at Ithaca College who major in Cinema with fantasies of transnational entertainment industry success, back in college I saw film as a powerful weapon of political struggle that merged radical insurgency, poetry, music, art, writing, and political analysis to carve out a more equitable world. I realized that film could create an open space for debate rather than the secretive discussions with the nuns.

As I watched The Janes, a big budget, Sundance Film Festival Grand Jury Prize-nominated film, I remembered these micro-budget political films from the Latin American solidarity and feminist movements that served a purpose larger than festival awards and streaming deals. Back in Iowa, it was impossible to imagine that films on these topics would roll on my computer screen at home, watched alone without discussion.

Although Roe has been overturned after almost fifty years, feminist film organizations have not been overturned. They are galvanized.

Women Make Movies and New Day Films are both more than fifty years old.

They emerged in the late 1960s and early 1970s from the women’s movement as it and other political movements worked to distribute independent film two decades before Sundance redefined independent film as a pick-up deal with a major distributor. These two groups have extensive lists of independently produced feminist films about reproductive rights, spanning decades, regions, and countries.

Pregnant

As I listen to “Dido’s Lament” for the fifth time as it blasts throughout the first floor of my house in Ithaca, New York, my thoughts twist back to Cindy.

A few weeks after meeting her boyfriend, Cindy was pregnant.

A group of IHMers, as we called ourselves, sat in the International House of Pancakes on Mannheim Road. We nibbled on pancakes drenched in fake maple syrup and gulped down bad coffee, figuring out what to do. Cindy stared into the parking lot, twirling her long brown hair around her fingers.

Thanks to one of our young male teachers who had gone to college “Back East” as we called it in the Midwest, Cindy connected with an IHM alumna a few years older who knew how to secure a legal abortion in New York City. It cost $200, plus airfare and hotel.

We pledged to chip in to pay for the abortion and travel costs, contributing money earned from our part-time after-school jobs at Sears, MacDonald’s, Burger King, and the local florist. We only had one week. Between the eight of us, we raised the money. Cindy flew to New York, her first time on a plane. We never knew if her parents knew. We never knew who went with her or if she went alone. She never shared any details about her abortion. She was silent, and so were we.

Months later, Cindy decided to get married. She enrolled in history and English summer school courses at Proviso West, the public high school, so she could graduate in December.

She pleaded with me to play piano at her very small wedding at Divine Infant Church. She was fierce: no traditional wedding music, no church organist, no Catholic hymns. I played the Bach Bouree and Gavotte from the French Suite in G Major.

I do not remember why I picked these pieces beyond my fixations on Bach and Baroque polyphonies. I practiced for weeks. My fingers and wrists swelled from the intense repetition to learn the sharps and flats in the music. My mother plunged them into ice in the kitchen sink to ease the pain.

Cindy took off with her new husband in his truck with the back part hacked for sleeping to explore the West.

She sent me a letter from Thunder Bay Ontario, writing that the moon shone blue light on everything below. The blue reminded her of our Catholic school uniforms—blue, gray, and white plaid skirts topped by dark blue blazers.

Laments

About six or seven years after Cindy’s abortion, I knelt in front of her closed coffin at her wake in a funeral home right across the street from the International House of Pancakes where my friends and I had collected money for her procedure.

I was in graduate school in communications at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, obsessed with political documentary, amateur film, experimental film — anything beyond commercial media. My network of intense feminist friends, endless debate about film and politics, and what seemed like endless demonstrations sustained me.

Cindy had divorced her second husband, with whom she had a daughter. She had been living in Phoenix, Arizona when her ex-husband smashed through the glass doors of their apartment and shot her to death.

The woman who shared her apartment was curled up in an overstuffed green velvet chair in the funeral parlor. She was so convulsed with weeping it seemed as though a backhoe had dug up her heart and soul.

“Dido’s Lament” is an aria that brought Cindy and abortion-before-Roe back to me. Cindy was laid to earth. I remembered her, as Dido asked.

“Dido’s Lament” is now a lament for the port city of Mykolaiv, Ukraine, whose mayor urges residents to leave because of the daily vicious shelling by the Russian forces.

It is a lament for the United States whose Supreme Court deliberately ruled to forget our fate, as Dido sings, and commenced a new war on women, who now must all be lionesses singing arias everywhere, together.

Patricia R. Zimmermann is the Charles A. Dana Professor of Screen Studies and Director of the Finger Lakes Environmental Film Festival at Ithaca College in Ithaca New York. The author or editor of ten books, her most recent are “Documentary Across Platforms: Reverse Engineering Media, Place, and Politics” (Indiana 2019) and “Flash Flaherty: Tales from a Film Seminar” (Indiana, 2021). Deepest thanks to Jane Banks and Noreen Sugrue.

Images by Gayatri Malhotra and Lorenzo Spoleti on Unsplash.